View Multimedia Slideshow:

The students came in wearing sweatpants — some of them carrying bags from McDonald’s for breakfast — and slouched down on the floor. The gym in what was once Stuyvesant High School, a building both grand and a bit run down, is now home to the High School for Health Professions and Human Services. The basketball hoops were low with scuffed brown backboards. In one corner, two men were clattering behind yellow “caution” tape, and the loud sound of a power saw cutting through the wood floor was broken only by hammering and drilling. The students didn’t seem to mind the noise, though, as they chatted with one another and found a seat in the center of the room for first-period gym.

At the same time, in a small gym above the girls’ locker room, where the walls are lined with posters of male athletes playing football and basketball, the lights were off. Nine Easter egg-colored yoga mats were spaced out on the floor and the 11th graders atop them were moving through a series of classic yoga poses such as sun salutations and downward facing dog. One boy, 17-year-old Jack Irving, grunted audibly and half the class erupted in giggles. But compared to the construction noises in the gym class below, the yoga session was serene.

In Manhattan, 77.6 percent of high school students do not attend daily physical education classes, and a quarter of students do not attend weekly classes, according to a 2009 report by the Centers for Disease Control. Manhattan has the highest rate of students not taking these classes out of all the New York City boroughs, followed by the Bronx. The state recommends students participate in an hour of daily physical activity, but few schools provide this for a number of reasons, including limited financial resources and time spent preparing for state testing.

While schools are failing to meet physical education requirements, the debate over childhood health has never been more tense. In the past 10 years, obesity rates have doubled, with more than half of all adults and school-age children in New York City considered overweight or obese, according to the city’s health department.

Against that background, more than 30 New York City schools are hoping that yoga will get the next generation moving.

The idea that yoga could be available in so many public schools seemed unlikely in 2000, when Jennifer Ford was teaching at-risk youth at a public high school in the Bronx. She was frustrated by her student’s inability to settle down in class. Ford, who was also a certified yoga instructor, began teaching her students yoga poses and breathing practices at their desks. The students liked it and yoga soon became part of the daily curriculum. When Ford met Anne Desmond and Courtney McDowell at a seminar on yoga instruction for prisoners, the three women began to conceive of a program that could bring yoga classes to schools throughout New York City. This was the beginning of Bent on Learning, a New York based non-profit that does just that.

“We were flying blind,” said Ford. “We learned very quickly, and the word spread really quickly, that there was free yoga teaching and a lot of schools didn’t have PE or PE teachers.”

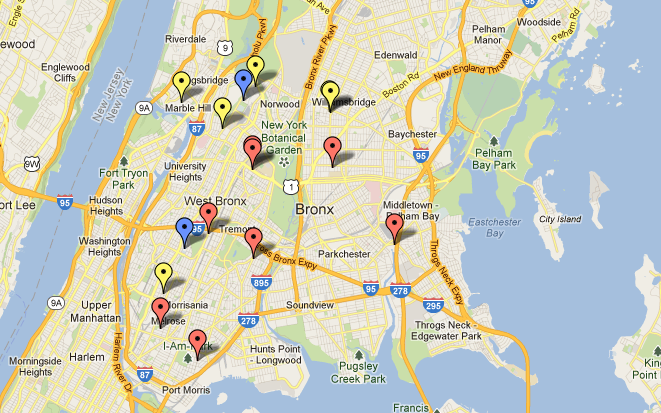

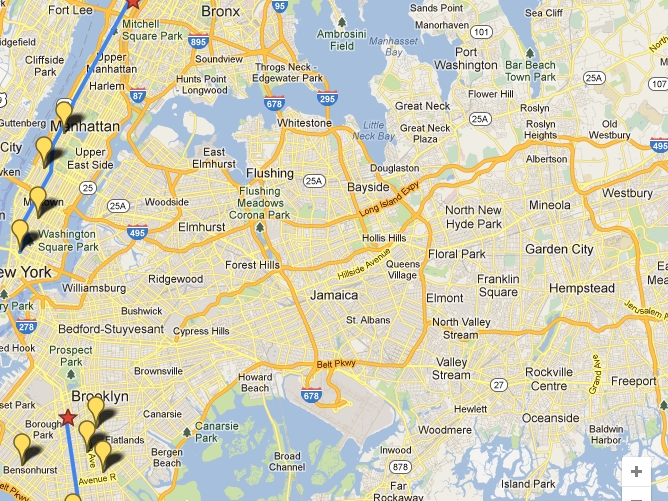

At first, the yoga teachers were friends and volunteers, but the schools were eager. Now through extensive fundraising and grants — Bent on Learning had a $500,000 budget last year — there are over 30 paid teachers in 16 schools, teaching an average of 136 classes a week, and 20 schools are currently on a waiting list to begin a yoga program.

At the High School for Health Professions and Human Services, Bent on Learning has 10 different classes offered each week for grades 6 through 12. On one recent day, the 11th graders seemed a mix of concentration and self-consciousness as they fidgeted with their clothing and hair and made audible jokes during awkward poses. But as the class progressed, their concentration increased.

“I think it’s good to be in shape and have a healthy body,” said Jack Irving after class. “It’s good to do this in-between classes…it keeps my mind at ease.”

Anastasia Netrunenki, 17, has been doing yoga for over two years. “I’ve really learned to calm myself at times and be aware of myself and how I am inside,” she said. She finds it especially useful when she’s feeling stressed, “which is common in high school,” she said. Netrunenki began practicing yoga at home to prepare herself for taking classes at school. Now she does 30 minutes of yoga each morning on her own before her hour-long commute to school from Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. Each Thursday, she takes the 45-minute class with her classmates. “Once I got into it, I started to really like it,” she said.

The benefits of yoga within a school environment are still being studied. For the past five years, the Kripalu Institute for Extraordinary Living (IEL), in partnership with Harvard Medical School, has been bringing yoga classes into high schools in Massachusetts to understand the relationship between yoga and well-being for adolescents. Over 1,000 students have participated so far. The results of these classes will appear in a new study in the Journal of Developmental & Behavior Pediatrics. Harvard researchers found that students who participated in yoga classes showed distinct improvements in sleep patterns, and anger and stress management compared to students who only took traditional physical education classes.

“The yoga provides an inoculation,” said Edi Pasalis, assistant director of the Kripalu Institute for Extraordinary Living. “It gives them tools to maintain their well-being over the course of the semester.”

Replacing physical education with yoga is not the goal but yoga could used to supplement gym classes and promote the emotional health of students, Pasalis said.

While yoga is movement-based, it does not provide the body with the same degree of cardiovascular exercise as more robust activities like running or tennis. Yoga also has been shown to lower metabolism. So while yoga can help students regulate their emotions, and as a result make better choices, it is not enough to fight adolescent obesity.

“If everything is equal, metabolically, yoga will make you fat,” said William J. Broad, New York Times writer and the author of The Science of Yoga. Through his research, Broad found that the calming properties of yoga caused metabolism to decrease as much as 18 percent in women and 8 percent in men. Yoga, however, may indirectly increase fitness. “In urban environments we eat because it makes us feel good,” said Broad. “Yoga helps de-stress you and can help break stress eating cycles and learn self-discipline.”

At Bent on Learning, children start learning these tools as young as age 3. One day recently in a preschool classroom at The Children’s Workshop School on East 12th Street, 17 children eagerly took their spots on purple mats. Chloe Tupper, a former Calvin Klein fashion executive turned yogi, began with the kindness pledge. The children crossed their arms over their chests in an “X” and recited after Tupper: “I will be kind to myself, I will be kind to my neighbor, I will be kind to my yoga space.” Then they picked grapes from the air and moved into downward facing dog, making gentle barking sounds to accompany the pose. “Wag your tails,” said Tupper. They moved into cobra and the class quietly hissed like snakes. Then they transformed their hands into seashells and covered their ears, inhaled through their mouths, and then exhaled through their noses to “buzz like bees.” The room hummed.

“Can two people tell me how they feel in their body?” asked Tupper.

“Funny.” “Weird.” “I feel droopy.” “I feel goofy.”

Then they moved into backbends.

“Is it ok if you fall?” asked one girl.

“It’s OK,” said Tupper. “Just come back up.”

After 40 minutes of yoga, the lights went off and it was time for corpse pose. The children squirmed, reluctant to be still and quiet.

“Everyone bring your hands to your belly so you can receive some jelly,” said Tupper. “I’m making a poem,” she explained. Then she walked around the room and softly tapped her finger on each student’s stomach.

“We have to wait for the magic,” she said.

Excellent writing and skillful reporting. I read the article twice!