In the Grand Ballroom of Midtown’s storied Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, roughly 700 New Yorkers applauded wildly on April 17 as seven city youths, raised in the margins of one of the world’s richest cities, shared stories about their upbringings.

At between $10,000 and $50,000 per table, the event was designed to raise money for Sponsors for Educational Opportunity, a 49-year-old program aimed at helping low-income students prepare for college.

One young man, who will be a freshman at Syracuse University this fall, talked about spending part of his childhood in a homeless shelter. Another girl told the audience that her family shared a one-bedroom apartment with six other relatives when they first came to New York.

As the crowd continued to pick at architectural appetizers sculpted from cylindrical vegetables, Evin Floyd Robinson took the microphone. He was the evening’s last student speaker. At 22, he was also the oldest Scholar, with almost four years of a liberal arts college education under his belt.

“On May 13th, I will give my mom the best Mother’s Day gift ever,” he said, delivering his remarks in a confident, firm cadence. “I will graduate from Syracuse University with a 3.5 GPA.”

After the dinner, Robinson climbed into a car service provided by the organization and headed back to his apartment on the outer edges of Brooklyn in East New York. The neighborhood is known more for its high homicide rate than its college graduation rates.

Last year, 29 people were murdered there, more than in any other city precinct. Median household income is just $30,700 a year, much lower than the citywide median of $50,285. Robinson has shared an apartment here with his mother and younger brother for almost a decade, just a few blocks from Cypress Hills and Pink Houses, two projects.

He lives in one America, and navigates another, with relative ease. “One thing that I learned growing up in the ghetto is that you have to know how to transition,” said Robinson, sitting across the street from the underground rumble of the Euclid Avenue subway station. “You have to know how to turn the switch.”

Robinson didn’t know Syracuse University existed before Sponsors for Educational

Opportunity got a hold of him. He graduated in 2008 from Science Skills Center, a public high school in Brooklyn Heights with 517 students where he said he “didn’t learn any science or skills.” He added that, although he is now approaching college graduation, most of his friends never even made it to high school graduation. Robinson was the exception, and that reflects the national reality.

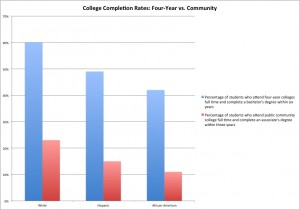

Federal statistics show that 30 percent fewer low-income high school graduates enter college than high-income high school graduates. And the differences are even starker for college graduation rates. A recent study by University of Michigan Professors Martha Bailey and Susan Dynarski found that, in the early 2000s, 54 percent of students from high-income families graduated from college, whereas only nine percent of students from low-income families did.

“They won’t earn as much. They’ll enter into low-income jobs,” said Cynthia Weissblum, President and CEO of the Edwin Gould Foundation, which attempts to improve college graduation rates for low-income students. “For me, there’s nothing more important than continuing with students to ensure that they do graduate from college.”

That’s one big reason why SEO aims to prepare its students for graduation from four-year colleges, not just enrollment. The organization reports that it has helped hundreds of low-income New York City kids graduate over its 49-year history. Its key method is requiring approximately 720 extra hours of instruction on Saturdays, after school, during breaks, and over the summer for targeted high school students who show college potential.

“The real victory is college graduation,” said Senior Program Manager Nicole McCauley. “Getting them through is the real part of it.”

Robinson needed no convincing to put in the extra time. He realized early that SEO was providing him with the guidance and support he needed to make it to college and leave his old neighborhood. It was not as smooth of a transition for two brothers in Red Hook, Brandon and Christian Serra, 17 and 14. Both stuck with it, however, and Brandon is about to set off for a four-year college. But several other low-income kids, if they pursue higher education, attend community colleges, where graduation rates remain significantly lower than those at four-year institutions. Rayfe Rodriguez, 19, took this route, and his efforts to stay in school have not been smooth.

“As Soon As They Let Me In, I Just Took Full Advantage of All the Resources.”

Robinson’s initial experiences with education were not especially promising. He took school seriously in some grades and not in others, based largely on how much he liked his teachers. But, thanks to his mother, he did learn one formative lesson early on that still encodes much of his thinking to this day: life exists outside of his neighborhood. And it seems like it might be worth checking out.

“Growing up in this side of Brooklyn, a lot of people don’t leave the area. That’s the biggest thing,” he said. “If you could take other kids and just give them a taste of college, that pushes them, and that inspires them to want to seek more.”

Robinson’s mother usually just took him on quick trips to Manhattan, where they spent time in places such as the Museum of Modern Art and SoHo. He gained even more exposure to life outside of Brooklyn after joining SEO in 10th grade. The organization provided him with multiple opportunities to leave the city, including a visit to Cornell and a summer at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business.

“As soon as they let me in, I just took full advantage of all the resources,” he said. “Whatever was going to put me in a position to enhance my education and enhance my possibilities in life, I was all for it, and that’s what SEO did.”

Robinson repeatedly says that there is no set way for youths in low-income neighborhoods to do what he did and make it to colleges like Syracuse. When discussing his own motivation, he credits not just his mother and SEO but also internal factors, such as refusing to give into peer pressure and feeling that he was “put here for a greater reason” (“not to get into spiritual and faith stuff,” he added apologetically).

However, he often returns to ignorance as a key problem among his peers, one that he hopes to use his college education to help solve. As someone who has already worked at companies such as JP Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, he is comfortable with the Waldorf-Astoria crowd. But his roots are still in East New York, something that becomes glaringly evident when the budding entrepreneur launches into a passionate, detailed discussion about his idea to transform the area’s community centers.

“Here, a community center equals recreation, so all you’re going to do is play basketball, a little kickball, a little dodgeball,” he said. “To me, a community center is a place where people come to learn, to build together, to broaden their horizons.”

Robinson envisions making community centers in East New York and similar neighborhoods more intellectual, multipurpose environments. In his opinion, they shouldn’t just be places to go play sports. They should be places where someone who’s interested in engineering can go to learn more about the subject and find out what it would take to turn this interest into a career.

It’s an ambitious idea, one that would require knowing how to bring in organizations with enough money and connections to help make such a transformation happen and an understanding of what it’s like to grow up in a low-income neighborhood in New York City.

In other words, it sounds like a task Robinson is perfectly suited for.

“When you’re young, you think everybody with a suit on is wealthy, you know?” he said. “But I learned how to adapt in those environments.

“But when I come back home, it’s regular to me now because this is my home,” he continued. “So it doesn’t feel any different to me.”

“There’s Stuff Beyond Red Hook. There’s Stuff Beyond Brooklyn.”

The Serra brothers have quite a few things in common with Robinson. They’re from a neighborhood on the outskirts of Brooklyn (Red Hook); they attribute much of their

educational success to their mother and to the college prep organization; and they were not always particularly motivated to take school seriously.

The difference is that Brandon did not automatically fall in love with the idea of going to class on Saturdays. In fact, he spent the bulk of his first year in SEO thinking about quitting.

“I was like, I don’t understand why I’m doing this,” said Brandon. “Where is it going?”

This attitude was not lost on his mother, who began feeling guilty for encouraging him to join. “It was too much for him at 13,” said Brandon’s mom, Yvonne Flores. “Going to school at night, going to school every Saturday, waking up early. It was a struggle in the beginning.”

His younger brother, Christian, was pleased he didn’t have to suffer through Saturday school, too.

“Seeing him come back, he would always look mad, frustrated,” Christian said. “It was just weird.”

The shift happened during the summer after 10th grade, when Brandon, who describes himself as “very competitive,” won an award from the college prep program. The reason? His teachers had named him the most competitive person in the organization.

The award was enough to help him finally understand why he was working so hard. He earned a scholarship to travel to Ecuador the next summer, which didn’t hurt either, even though he estimates he had to write about seven essays for it.

“That’s when I started to see it,” he said. “I was like, ok, some essays I wrote did help, and I can use those for college.”

After that, his mom said, he would go willingly to classes at SEO and was much happier for it. “It was a blessing,” said Flores, “because at first I thought I was going to lose him.”

Brandon, now a high school senior, was accepted into DePauw University in Indiana, where he will enroll this fall. He would like to see more kids from Red Hook do the same, and his idea for how to make this happen is straightforward: he thinks they just need to see more people like them going.

“There’s stuff beyond Red Hook. There’s stuff beyond Brooklyn. There’s stuff beyond New York,” Brandon said. “I will come back here and talk about college like it’s no tomorrow.”

Brandon may not have spread this message throughout Red Hook yet, but he has already had some success with it in his own household. Christian is now enrolled in the same organization that intimidated him just a few years ago. And the reason he gave for his turnaround was because he saw what it did for his older brother: namely, got him a chance to go to DePauw with a scholarship.

“Just seeing my brother go to SEO, and again, just seeing him actually getting that scholarship,” he said. “I was like, wow, my brother’s going to DePauw University. And I want to make him proud.”

“Sometimes I forget that I was even in school.”

Rayfe Rodriguez devours books such as Robert Kiyosaki’s Rich Dad, Poor Dad and

Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich. He enjoys talking about the differences between active income and ongoing income. He is frequently well dressed and well spoken, and his favorite periods of American history are the Civil War and the Roaring ‘20s.

And he might be going back to college next fall.

“I will. I might. I’m not sure,” he said. “I’m still making the decision.”

Rodriguez graduated from high school last year, enrolled at Bronx Community College in the fall, and did not return in the spring. His reasons for not coming back provide a textbook example of the types of problems community college students often face: he had issues with his financial aid; he had work and family obligations to worry about on top of his classwork; and he felt virtually no sense of community with the institution.

“Generally speaking, community college students are balancing a lot of life circumstances,” said Donna Linderman, University Executive Director of CUNY Accelerated Study in Associate Programs, a program meant to help community college students graduate as quickly as possible. “They’re working, they have domestic responsibilities, and they’re going to school. So balancing all three of those is difficult at times, and it’s one of the reasons that community college students will stop out for a semester or two.”

This is essentially the exact situation Rodriguez was in while at Bronx Community. Because his family only had one set of keys, he would often have to leave school early so his mom could get back into their house. And to help pay for some essentials like transportation and food—Rodriguez would often walk from his home to school because he couldn’t afford a MetroCard and said there were also days when he “just didn’t eat”—he started working at a Macy’s in Chelsea toward the end of the semester.

It was thus difficult for Rodriguez to consider the classes he was taking at Bronx Community his number one priority, especially when he never felt like he truly belonged there in the first place. He does not describe his time at the institution with the fondness of

a devoted alumnus; rather, he describes it as something he fell into because he was a high school graduate, and college is where high school graduates are supposed to go.

“Sometimes I forget that I was even in school,” he said. “I didn’t even feel like my presence really mattered there.”

Rodriguez does not place the same level of importance on education as Robinson or the Serras. He talks about being aggravated with teachers and assignments throughout elementary, middle and high school for not teaching him useful information, and he enjoys bringing up businessmen like Mark Zuckerberg as proof that a college degree is not a necessity for a successful career.

“School wasn’t really for me,” he said. “I just felt like it wasn’t teaching me anything I wanted to know.”

Still, he maintains that he will likely return to Bronx Community in the fall so he can at least have something to fall back on. He doesn’t plan on giving up his job at Macy’s, and he isn’t sure where he’ll be living yet, but he is still optimistic about staying for longer than a semester this time. He plans on being more sociable to help him find that sense of community he initially missed out on, and he plans on returning with a better sense of what he hopes to get out of his education to give his time at college more purpose.

“I had one,” he said, referring to a goal when he enrolled last fall. He paused before adding, “I should’ve wrote it down.”

Coach Roy Williams’ North Carolina Tar Heels up and running their period rated #one and finished their year #one with their fifth National Championship as North Carolina easily conquer #two-seeded Michigan State 89-72 in the only activity that counted-the match to decide the nation’s most desirable group for the 2008-2009 season.

Santa Maria, Ca.

There are certainly a lot of details like that to take into consideration. That’s a great point to bring up. I offer the thoughts above as general inspiration but clearly there are questions like the one you bring up where the most important thing will be working in honest good faith. I am sure that your job is clearly identified as a fair game.

Thanks for sharing