Maria Vasquez was nervous. The high school senior walked into the college counseling room at her school in the South Bronx one Friday afternoon in late March. She logged onto the computer. Waiting for her was a message from New York University.

Vasquez, 18, anxiously opened the email, paused in confusion, and then jumped for joy. On that day she became the first person in her family who will attend not only college, but her dream school. The dogged assistance of her school’s college counselor–the kind of one on one attention that is hard to come by in many of the city’s high schools–had helped propel her to this moment.

“I was super excited,” said Vasquez, who has attended Urban Assembly for Applied Math and Science since the 9th grade. “At first I didn’t know, because it didn’t say congratulations.”

Navigating the complicated landscape of college admissions and financial aid can be cumbersome for any student. The process is especially arduous for first-generation, low-income students and children of immigrants. A 2011 Princeton study reveals that immigrant enrollment in college has decreased over the last decade. A recent Stanford University study suggests that low-income students typically either downplay the odds by applying to less selective schools, or don’t apply at all.

But for students like Vasquez, who are enrolled at Applied Math and Science, the odds are changing. Over the past six years, college entrance for New York City high school graduates has shot up 10 percent, according to city records.

Nationally, more than half of low-income students are enrolled in college and overall college, enrollment for low-income students has generally increased over the past several decades, according to data from the 2013 Digest of Educational Statistics. However, due to the lag in the economy, a Pew Research Center study suggests, the gains of recent years have stalled and more middle- and upper-income students are far more likely to enroll in college.

President Barack Obama has tried to address those concerns through a number of policies. His administration pushed Congress to increase the maximum Pell grants designed for low-income students, awarding them to an additional three million students since 2008, and created the American Opportunity Tax Credit to help low-income families pay for college.

A 2009 report conducted by the Pew Center for Economic Mobility concluded that “unless something is done to boost the number of young people earning postsecondary credentials, millions of Americans will continue to be limited in their economic mobility.”

Inside the kaleidoscopic halls of Applied Math and Science, school officials are trying to buck these odds by creating a pathway for its more than 600 low-income and minority students to go to college.

The school is located on Bathgate Avenue in the heart of one of the city’s most impoverished areas. Nearly 40 percent of its residents live below the poverty line. For children, the poverty rate is double that in other city neighborhoods, according to a report by the Citizen’s Committee for Children. And in the neighborhood, only 4 percent of the nearly 160,000 residents have at least a bachelor’s degree.

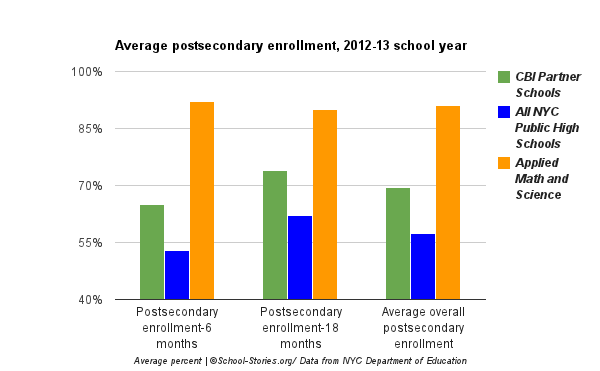

Vasquez’s chances were boosted just by being at AMS, where 91 percent of graduates enroll in college. That’s 20 percentage points higher than the citywide average, according to the most recent 2012-13 school data from the NYC department of education.

One reason for the school’s success lies in its robust college counseling program provided through the CollegeBound Initiative, a nonprofit that places full-time college counselors in 21 public schools that serve low-income and minority students.

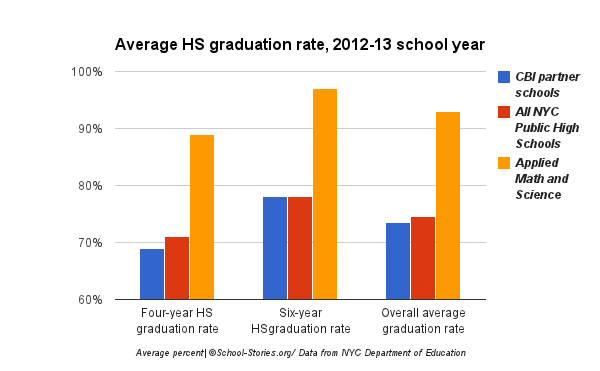

Recent city data show that the average high school graduation rate for New York City’s 290,000 high school students is 75 percent. In the schools that partner with the CollegeBound Initiative, the average is slightly lower, but their college enrollment rates outpace the citywide average of high schools by a dozen percentage points.

Nationally, the racial gap in college enrollment overall has become narrower: 67 percent of blacks and Hispanics in 2011 enrolled in college compared to 68 percent whites. But minority college enrollment has noticeably lagged in the nation’s most selective colleges. Only 7 percent of blacks and 10 percent of Hispanics made up 2009’s freshmen at the top 438 colleges in the U.S. For white students, it is 72 percent, according to a report by the Georgetown Policy Institute.

The serious dearth of high school college counselors is believed to be a contributing factor. The CollegeBound Initiative aims to change that.

Vasquez is part of more than 11,000 high school students who receive assistance from the nonprofit. In a school system where the city comptroller found that more than half of its high school students have one counselor for every 250 students, College Bound Initiative helps fill a crucial need.

The comptroller found that counselors’ large caseloads make it impossible to provide the kind of academic, logistical and socio-emotional assistance needed to pursue a college degree.

Jatae Daly is the CBI college counselor at Applied Math and Science, a popular 6th through 12th grade school designed to provide

rigorous curriculum in every subject and particularly in practical math and science. Her caseload clocks in at a little over 80.

“Some counselors only care about helping students with the higher grades,” said Vasquez. “In this school, the counselor helps everyone.”

Daly has observed that some schools just focus on the A students.

“I try to give equal time and equal work,” she said. “I really build a special relationship with them,” she said. “For a lot of kids, getting out of the South Bronx is important.”

Among her duties are scheduling SAT and ACT prep sessions, planning visits to college campuses, assisting with financial aid forms and personal statements.

The CollegeBound Initiative was launched in 2001 at the Young Women’s Leadership School in East Harlem, the flagship public school for all girls. Director Jon Roure said he wanted to create the service because so many schools serving low-income students did not have college counselors. Due to staff shortages, many schools double up their guidance counselors or deans, which cuts back their effectiveness.

“We want to be the missing link,” said Roure, who started as a counselor at CBI and was then tapped by the organization’s founder to expand the program to co-ed public schools in New York City, and quickly rose to become the organization’s leader. “We want to create a buzz around college.”

To date, CollegeBound counselors have helped almost 6,000 students enroll in college and received nearly $90 million in financial aid, according to the organization’s website.

The organization is funded by JP Morgan Chase, the Robin Hood Foundation, an anti-poverty organization with roots in the hedge fund world, and a number of government grants. Currently, the program favors schools that primarily serve grades 6th through 12th.

The plan is to place counselors in public schools by building what Roure calls a “healthy relationship” with the Department of Education and the previous and current administrations in the mayor’s office. Roure said CollegeBound Initiative has a plan to expand to 35 schools over the next three years. He also cites a 94 percent graduation rate since 2001 for the students who have been in its partner schools.

Daly came to Applied Math and Science in 2011 from New York University, where she worked in the admissions office as an undergraduate work-study student. At NYU she worked with their STEP program, which allowed her to work with students, and give them guidance, advice and counseling.

Daly said she could have used this kind of help as a high school student. She grew up in the South Bronx, blocks away from Applied Math and Science, and knew personally how hard it was to make it out of a working-class community and end up at a top university. She attended John F. Kennedy High School in the Bronx, which serves a similar population as Applied Math and Science, but whose current college enrollment rate is a full 40 percent lower.

While in high school, Daly maintained a high average, but said that counselors advised her to apply to community colleges. She ended up at New York University by creating a random list of colleges that she would apply to on her own. By good luck and merit, she was admitted along with a healthy financial aid package designed for low-income, first-generation students.

“If I were wise, I would’ve expanded my list,” she said.

Eventually, she made the leap from working at NYU to joining the CollegeBound Initiative. Now, in her third year as a counselor at Applied Math and Science, she said she tries to tap into her personal experience when she advises her students.

Daly said she works diligently to get her students to consider a wide range of options from community colleges to Ivy League universities to create opportunities for growth for the school’s high-achieving students and students with low averages.

“Some students have their dream schools,” she said. “But sometimes we have to sit down and look at their grades and scores and re-adjust our strategy.”

That strategy sometimes results in having to steer them from an unrealistic dream school to another great school with which the student is likely unfamiliar, such as Gettysburg University in Penn., where one of their recent graduates ended up and received a generous scholarship.

“Our students sometimes get caught up with brand name colleges,” she said.

Daly finds her work infinitely rewarding.

“It’s great to have people who are the first in their family to attend college,” she said. “Some are even the first in their family to graduate high school.”

Daly said that she attempts to bring as many students as possible into her office, which is outfitted with college posters and banners, brochures, test preparation materials and a bank of computers. The visual reminders are all in an effort to drill in the importance of college, especially for those who are not thinking about it.

While commuting to work one day, she found out that March 6th was “National Oreo Day.” She then stopped in a nearby bodega and bought some to bring to school. Daly said she used that opportunity to bribe her juniors at AMS to register for the SAT and get their college admissions paperwork in order.

“For a lot of them it’s easier to get discouraged,” she said. “[We work] with students with the highest engagement and meet them on their level. It’s really rewarding work.”

For Vasquez at AMS, her passion lies in education, and at NYU she will focus on early childhood education.

“I want to change the education system because I feel that there are many injustices,” she said.

“Things people should have learned in elementary school, they don’t know in high school,” she continued. “I noticed people around me did not know proper grammar.”

Higher education long has been seen as one of the best ways to change the life trajectory of the struggling urban poor.

Looking deeply at the CollegeBound Initiative, it believes that the answer to that creating a clear pathway to college for many low-income students is the best way out of poverty and better socioeconomic attainment.

Dion Reid, a CollegeBound Initiative counselor at the Young Women’s Leadership School in East Harlem said that in his two years encouraging low-income, first-generation students to apply to college he has seen time and time again, that the personal connection can make all the difference

“The most fulfilling moments I have experienced are often when students who did not believe they would be able to attend college find the courage and confidence to reject their conditioning and believe in themselves,” he said via email.

The demographics and socioeconomic makeup of East Harlem mirrors that of the South Bronx. And Reid’s own story connects with the populations he serves.

His father was in jail for Reid’s entire childhood, and later died before he could be released. His mom worked fulltime for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

“She had to work a great many hours in order to ensure that bills were paid so she always stressed that I had to work hard in order to help her help us,” he said.

Reid participated in many college preparatory programs and focused on his education.

“My mother trusted me to find the resources I needed to apply to college and be successful,” he said.

Reid attended Wesleyan University where he decided that his mission would be to find a way to offer the same opportunities he had to other students from the Bronx and similar environments.

And it’s all in the one-on-one relationships, he believes.

“I find that once a student trusts that you sincerely care for them, they believe that they can be a better person.”