Photo Credit: RUBEN RODRIGUEZ/UNSPLASH

When New York City became the epicenter of the coronavirus in early March, leaving all public schools shut down in its wake, one stalled project for the city’s students living with physical disabilities found a moment of opportunity.

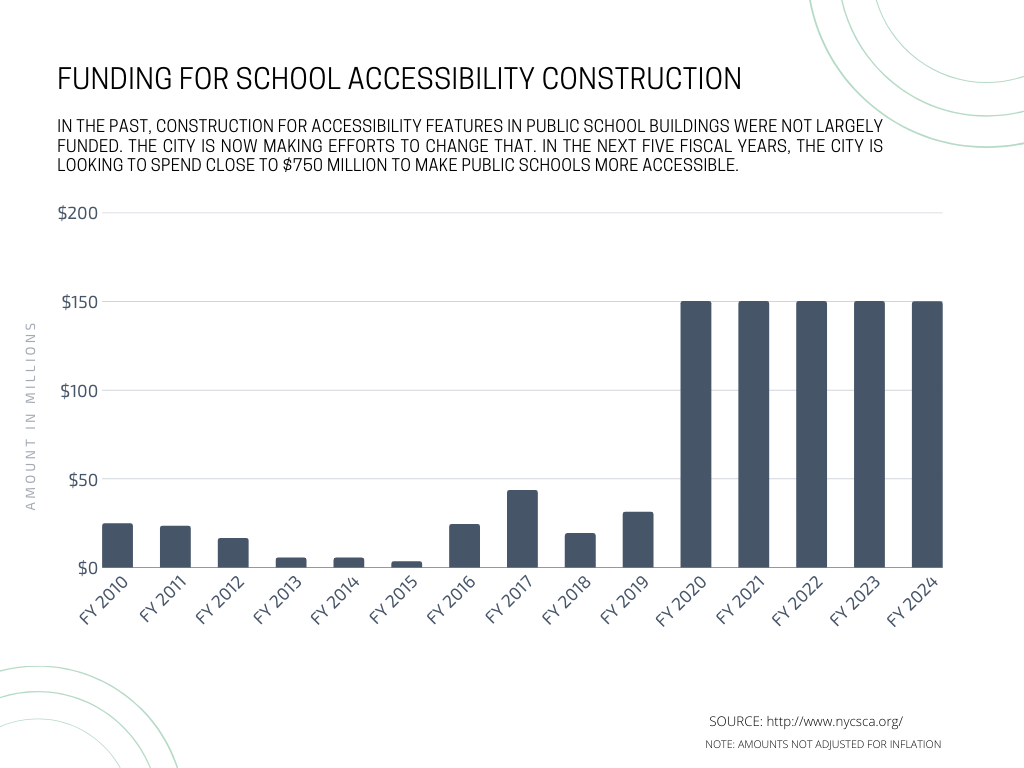

With empty schools, the New York State School Construction Authority’s $750 million projects designed to make the lives of students with physical disabilities easier could continue, and perhaps be completed.

In 2018, a report by the nonprofit organization Advocates for Children found that more than 80 percent of public schools surveyed by the Department of Education were not fully prepared to serve students with physical disabilities. These schools lacked wheelchair ramps, elevators, and handrails. At the time, only 335 out of more than 1,800 schools in all five boroughs were totally accessible.

In fact, the aging city school infrastructure has had hundreds of buildings out of federal disability compliance for decades. The problem worsened as the number of co-located schools increased – the result of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s policies to break up large schools and create small ones – including hundreds of charter schools placed on the top floors of school buildings. It took a scathing federal investigation five years ago to finally force the city to upgrade their buildings for handicapped children.

Current Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has since vowed to make half of all elementary schools at least partially accessible by adding certain features such as wheelchair ramps and handrails, and a third of schools completely accessible by 2024.

Construction on school projects in schools like I.S. 35 in Brooklyn, Fiorello LaGuardia High School in Manhattan and P.S. X811 SPED in the Bronx were all active through early February according to New York City data. These projects are part of a plan to give students with disabilities more choices, said Maggie Moroff, the Special Education Policy Coordinator for Advocates for Children.

“The problem is now that all of that has stopped,” she added.

As the death rate from Covid-19 surged in New York State from nearly 500 in the first week of March to 914 deaths in one day on March 30, the School Construction Authority announced that all non-essential construction projects were put “on pause until further notice,” leaving advocates worried about all the students who are depending on the competition of these projects.

School accessibility has been an enduring, decades-long problem in New York City. Five years ago, the city’s school system was accused by federal prosecutors of having an “abysmally low percentage” of school buildings accessible to handicapped children.

When the city’s capital budget for 2015-2019 was first proposed in early 2014, advocates knew almost immediately that there was a noticeable gap in proposed funding to bring city school buildings into compliance with federal accessibility laws. While the budget allowed for $100 million for construction of ramps, elevators and bathroom upgrades, the amount totaled less than 1 percent of the Department’s behemoth budget.

A year later, Preet Bharara, the former United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, published his federal investigation findings in a scorching letter.

“Our investigation revealed that 25 years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the City is still not fully compliant, and children with disabilities and their families are being denied the right to equal access to a public-school education,” Bharara wrote. Overall, according to the Department of Justice, for more than 50,000 students in New York City, attending a local school was not possible because they did not meet their needs.

According to the audit, wheelchair bound students in P.S. 140 in the Bronx found an auditorium with 408 fixed chairs but not a single space where their wheelchair could fit comfortably. The school had four floors that were completely unreachable from the main entrance because of a small set of stairs, and water fountains low enough to tease wheelchair bound students but high enough to be just out of reach. In one case, investigators interviewed a family that were through extreme measures to keep their daughter in their community school, including carrying her “up and down stairs to her classroom, to the cafeteria, and to other areas of the school in which classes and programs were held.”

The DOJ demanded action from the city, stating that it had to end “the practice of ignoring the Americans with Disabilities Act” and address the inaccessibility issues plaguing public schools. But three years later, in October 2018, Advocates for Children of New York found that progress towards addressing this problem was stagnant and published their findings in a report titled, “Access Denied.”

The report found that in order to truly fix all the prevailing accessibility issues, the city would need to dedicate an estimated $850 million over five years. This amount of money, the report said, could fund special projects to help students with mobility, hearing, and vision needs finally feel included in their school community.

The first major push Moroff and her colleagues tackled was getting a list of accurate school profiles that could inform students and parents of any accessibility issues they might encounter at any of the city’s 1,700 schools.

“For students going through the admissions process, entering kindergarten, middle school, or high school, finding the school that could meet their accessibility needs was next to impossible,” Moroff remembered. “We talked to families who would go on tours and couldn’t get through the front door or couldn’t continue the tour past the entrance because there was no way of getting up to the second floor.”

Together with the DOE and the advocacy community, the city deployed a team of inspectors to school buildings and developed new and readily available building profiles that rated how accessible school buildings actually were. “We wanted more access for families and we wanted more information for parents,” she said.

Jaclyn Okin Barney is a disability rights lawyer who worked with Advocates for Children in their push to get more funding for projects like elevator repairs in schools. Three years ago, she says the “stars aligned” for the DOE to throw its support behind addressing accessibility problems in schools.

“Most kids are encouraged to list 10 schools when applying to high school, but at the time, kids with disabilities couldn’t even list 10 schools because there were so few accessible schools – they didn’t have choices,” Okin Barney recalled.

Through continued advocacy work, Okin Barney said the Department of Education has made progress to try to meet student needs. Recently, she said officials took a step in the right direction by putting a policy in place ensuring students with physical needs were granted admissions priority for their first rated school. And while Covid-19 has halted much of the progress planned at making public schools more inclusive, Okin Barney believes the Department of Education remains committed to the issue.

“There are more pressing issues to take care of right now, but we’re still working toward our goals,” she said. “I think the DOE deeply understands the importance of this issue.”