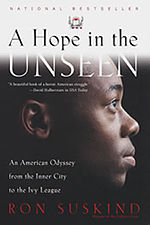

Ron Suskind’s “A Hope in the Unseen” opens as Cedric Jennings memorizes SAT words in his Washington, D.C. classroom rather than attend an assembly where his name would be called—and he would be mocked—for being an honors student.

Ron Suskind’s “A Hope in the Unseen” opens as Cedric Jennings memorizes SAT words in his Washington, D.C. classroom rather than attend an assembly where his name would be called—and he would be mocked—for being an honors student.

Such is how Cedric lives as a student attending Frank W. Ballou Senior High, described as “the most troubled and violent school in the blighted southeast corner of Washington, D.C.” He mostly keeps to himself and dodges insults in the school hallways. Second in his class, he aims to attend MIT, where he is accepted into a summer program for high-achieving minority students. He struggles with academics as well as his identity over the summer, as he realizes he faces many challenges unknown to other, mostly suburban, students. Advised not to apply to MIT after his summer performance and low SAT scores, Cedric continues to strive for a rigorous college experience and is accepted early action to Brown University.

Brown’s atmosphere, with its many privileged students and emphasis on multiculturalism, sharply contrasts with Cedric’s experience of poverty in Washington’s inner city. “Really is a whole ‘nother world up here,” remarks Barbara Jennings, Cedric’s mother. But Cedric’s parents have shaped his role as a man in society and his striving to be a strong student. Cedric does not want to be like his father, who is in and out of jail. Cedric’s mother raises him to be a man of faith, taking him often to church; but Cedric also acts as the man of the house.

The book shows that his parents are living in the shadow of their own pasts. When Cedric’s father, also named Cedric, contemplates sending his son a letter mentioning how he first thought his son was “shooting too high” when he wanted to go to Princeton, the father reflects on his own father leaving the family when he was seven. Barbara and Cedric also talk about how Barbara used to be good at school. Barbara has many responsibilities; she works for the government and tries to make a living, but went on welfare to have time to raise Cedric when he was young.

As Cedric grapples with his identity at college, new friends act as foils to his struggle for self-awareness and his understanding of race. He clashes with his white roommate, Rob, who comes from a homogenous suburban background. His friend Zayd, who is white and the son of Weather Underground activists, becomes his close friend, but they argue. Zayd attended a Harlem school where some black students bullied him. Cedric asks how he cannot hate black people now, but Zayd remarks that not everyone of the same race is in fact similar. His friend Chiniqua, who attended Prep for Prep in New York City, also remarks that people of the same race can hate each other as much as people of different races. Cedric struggles when he sees wealthier, suburban black students adopting black, inner-city culture: he knows he cannot be friends with them, because they don’t understand what the clothing and symbols signify.

Cedric also must come to terms with the fact that his educational experience did not offer him the same opportunities and rigors as many of the more privileged students. Cedric struggles in most classes, but he excels in calculus, which he methodically studied at MIT. In his education class, he analyzes an inner-city school, similar to his own, where suspensions are common and a teacher remarks that one can tell who will soon die after leaving school. Cedric is disturbed – “he’s writing them off before they even get a chance.” This comment goes to the heart of Cedric’s philosophy of life. The circumstances in which one is born cannot proscribe the future: there is hope in the unseen.

Cedric rejects certain childhood limitations and becomes more confident in his identity as he attends college. He realizes at college that pride in himself—which was discouraged at church and criticized in high school—has enabled him to accomplish his goals. “ Though he’d never actually use the word, kids must have sensed it in him when they always attacked him for “thinking that he was better than everyone else.” He ended up building all those convoluted rationales for lofty ambition, saying he needed to go to a famous college, a place everyone had heard of, to justify all his painful sacrifices. It’s all clear now: that was just a cover. “It was pride—pure, simple, in your breastplate pride—that got him to this place.” When Cedric returns home and finds that his mother never told him that she was behind in the rent and is now being evicted, he remarks that “this is the sin of pride.” Cedric has kept the values that his mother and the church instilled in him, but he has redefined them to align with the self-knowledge he has gained.

Suskind allows the reader to get inside of Cedric’s head as he struggles and succeeds from poverty to Brown University. As Cedric wonders why his potential success—or failure—means more to society than just one young man’s journey, the book raises a debate about how the personal intersects with the political. Through Cedric’s eyes, “A Hope in the Unseen” surfaces thought-provoking questions of race, gender, identity, and how we interact with each other.