Psychologists agree: suspending kids from school doesn’t work. If the goal of the suspension is to help students learn how to control their behavior so they can learn better, then suspensions are the wrong tool. In fact, what suspensions do most reliably is predict future suspensions, according to the American Psychological Association. If a child has been suspended, he’s likely to be suspended again, and again.

There are multiple reasons behind this cycle. Students who are suspended often fall behind academically. “You miss homework, you miss tests, and often in high suspension schools, there aren’t a lot of supports for getting you back on track,” said Michelle Fine, psychology professor at the City University of New York.

Students who are repeatedly suspended begin to feel alienated from the school environment. “Over time, kids either get the feeling that they are not welcome or don’t belong there,” said Fine. She noted that this is especially the case with younger students, who begin to perceive themselves as a “bad kid.”

Brandi McNeil of the Suspension Representation Project, an organization which defends students at suspension hearings, has noticed a sense of ambivalence and distrust in many of her clients. “Some kids really don’t care,” saidMcNeil. “You see that a lot more often with kids who have been suspended multiple times.” Rather than helping to modify behavior, suspensions simply remove students from the school environment, and when they return, nothing has changed.

“Kids with behavioral problems are under-responsive to punishment and over-responsive to reinforcement,” said child psychologist Stewart Pisecco. Rewards for positive behavior work much better, he said. Teachers can provide clear expectations, structured environments and procedures and solid, trustworthy relationships.

More importantly, though, Pisecco said prevention is key. “The reality is that these were kids that were challenging to their teachers in elementary school,” he said. “We wouldn’t wait until the middle school years to start identifying kids who need academic interventions. So why is that okay with behavior?”

Pisecco believes testing and monitoring should be applied to students’ behavior. He runs a software company that provides materials and techniques to help schools deal with behavioral problems. “The issue of improving behavior in schools has to be elevated to a higher level,” he said.

The New York City Department of Education’s discipline code recognizes that students should receive support services while they’re on suspension, such as counseling, peer mediation and parent outreach. Nevertheless, McNeil said her team at the Suspension Representation Project rarely observes these steps in high-suspension schools. “If things ran the way they were supposed to run, obviously things wouldn’t be perfect, but I think they’d be a lot better,” she said. “They are not actually implementing the discipline code as it was intended by whoever sat down and wrote it.”

The problem is that these measures take effort, time, and money. Pisecco does not give his software away for free. Schools with high suspension rates are often low on resources, and rely on school security officers to handle behavioral issues.

“There has been a real increase in school safety officers,” noted McNeil. “Instead of having issues that traditionally would have been dealt with by a phone call from the principal, now a student is getting arrested automatically for a fight”

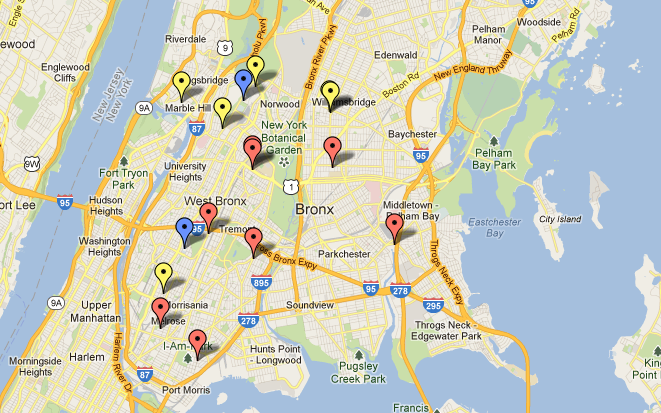

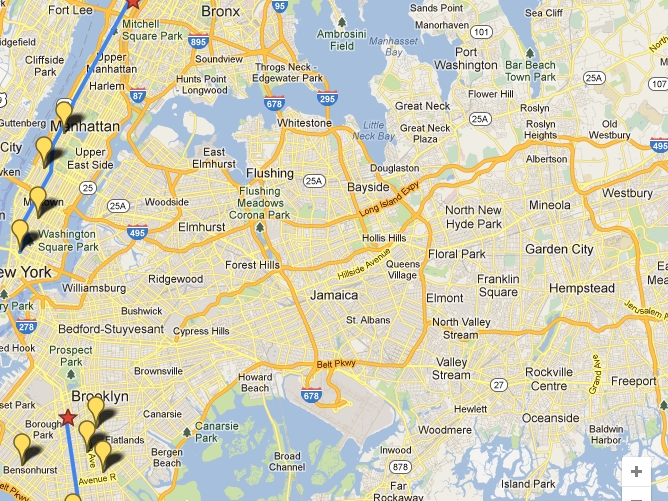

In January 2004, the mayor launched the New York City Impact Schools initiative, which assigned 200 NYPD security officers to 22 middle and high schools with high incidents of criminal activity and low attendance rates. Suspensions at these schools were higher than average before the initiative. They increased 45 percent over the year and a half the security officers were present. According to a report by the Drum Major Institute, these schools were overcrowded, underfunded, and served a disproportionate number of poor students.

“I think there is a tendency tolook at schools and school officials as being these malicious people who are out to get students, and I don’t believe that’s the case,” said McNeil. “I think more than anything, there’s not the knowledge of what their options are, and—whether it be money or time or energy—there’s not the resources to dealwith students effectively.”

Michelle Fine recognizes that poorer schools have the disadvantage when dealing with students with behavioral problems. “Upper-middle-class kids will do fine because everybody will buy themout of their problems,” she said.

Nevertheless, Fine believes that students who are frequently suspended have the potential to turn around whenplaced in a supportive, respectful setting.

“When kids feel respected, it’s kind of amazing how cumulative that is, and how they then become the guardians of school safety, security, and respect,” she said. “In the right context, kids really want to learn.”