While many boys his age were playing video games or sports, a 14-year-old from Bangladesh spent every Saturday afternoon since last summer studying math and English at Khan’s Tutorial, a test preparation center in Jamaica, Queens.

Joydeep Baidya, an 8th grader in Intermediate School 238 in Jamaica, said he had no regrets, when he found out in late March that he scored 592 out of a possible 800 on the New York City Specialized High School Admissions Test, high enough to gain admission into Manhattan’s Stuyvesant High School, one of the city’s top public high schools.

“For the period leading to the test, the priority was not fun,” said Baidya, who moved to New York just three years ago. “It was to pass the test.”

Baidya is one of the 161 students at Khan’s Tutorial this year who secured a spot in the much-coveted specialized high schools in New York City. The majority of the 200 students who registered at Khan to prep for this year’s test were born in Bangladesh or are children of Bangladeshi parents. Just like their Chinese and Korean counterparts, Bangladeshi families put great emphasis on education and testing is deeply rooted in their culture. The students are quietly becoming sought after by test prep centers in Queens and beyond.

According to Ivan Khan, Chief Operating Officer of Khan’s Tutorial, the test prep center has been sending more than 100 students to the specialized high school every year since 2005. About 30,000 8th and 9th graders take the test every October, and roughly 5,400 are offered admission into one of the eight elite schools, including Stuyvesant, Bronx High School of Science and Brooklyn Technical High School. Khan said the enrollment in his center has gone up 20 percent this year and he had opened two new branches just within last two years.

In recent years, Asians have made up the majority in the city’s specialized high schools. Stuyvesant’s 3,300 students in grades 9 to 12 are 72 percent Asian, 24 percent white, 2.4 percent Hispanic and 1.2 percent black. Although the majority of the Asian students are either Chinese or Korean, the Bangladeshis are making impressive progress.

“When I went to Bronx Science, there were maybe six or seven Bangladeshi students per grade,” said Khan, class of 1999. According to one of his former students, Ishraq Chowdhury, class of 2012 at Bronx Science, about 13 to 15 percent of the school’s total population of about 3,000 students are of Bangladeshi descent. The school did not return requests to confirm the numbers.

One obvious reason is the rapid growth of immigrants from Bangladesh. According to census statistics, the number of Bangladeshi immigrants has grown more than10 times in the last two decades, from about 5,000 in 1990 to close to 60,000 in 2010. New York City is their number one destination.

Nazli Kibria, a professor of sociology at Boston University who studies the Bangladeshi diaspora in the U.S., said most Bangladeshi immigrants left their country to improve ther economic and educational opportunities.

“It is a driving force,” said Kibria. “The emphasis on education gives meaning to their immigration to this country.”

The London-born Khan spent a year and a half of his youth in Bangladesh. He said performing well in school is a source of pride and joy for Bangladeshi families.

And the emphasis on education cuts across class lines. According to Khan, many parents who send their children to his test prep center are blue-collar workers, ranging from cab drivers and restaurant workers to shopkeepers.

“But the drive to help their children get into one of the most competitive schools is just as strong as middle-class parents,” said Khan.

Among the Bangladeshi-run test prep centers, Khan’s Tutorial is the largest and most established. Founded in Jackson Heights in 1994 by Khan’s father, a former public school math teacher and assistant principal, it now operates in six locations in New York City and one in Long Island. The newest location in Astoria opened last year. It has attracted many non-Bangladeshi students, including Eastern Europeans and Middle Easterners. In addition to the program for specialized high schools, Khan’s also offers prep programs for the SAT, Regents Exams, Advanced Placement courses, and summer programs for kindergartners through sixth graders.

“We advertise through the Bangladeshi satellite television that goes out to the rest of the country,” said Khan, referring to Bengali-language satellite channels made available through the Dish Network in the U.S. “Now we even get requests from California. But we want to maintain the quality so we have no plans to expand outside of New York.”

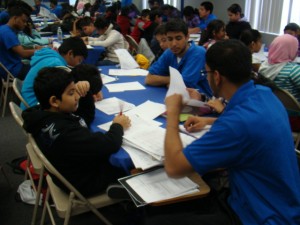

On a recent Sunday afternoon, dozens of students were getting ready for the upcoming Regents Exam in Khan’s modest four-room center located above a Bangladeshi deli and Guyanese restaurant on Hillside Avenue in a commercial section of Jamaica. Many of the 17 seventh graders in Roman Patwary’s math class had their hands up, eager to solve an algebra problem on the blackboard. In the room next door, students of various ages worked with tutors in small groups on English and math exercises. Many instructors and tutors in the prep center are former Khan’s students who went to specialized high schools themselves.

Instructors say their center prepares students “for a future of standardized tests.” Niloy Iqbal, a premed student at New York University who has been teaching at Khan’s since 2009, ticked off all the exams students need to enter professional schools in medicine, law and pharmacology.

Meanwhile, Iqbal said the content for the specialized high school test does not go beyond what students learn in school.

“The material is taught in school,” said Iqbal, who attended Khan’s and got into Stuyvesant. “It’s just the way they pose the questions. It’s forcing the students to think critically.”

Khan’s charges a flexible rate of $75 per week for a four-hour session. Students received a reduced rate if they sign up for long-term classes. The center offers a $3,500 package of 52 sessions and 20 workshops that comes with a guarantee of admission into a specialized high school. Khan said about 90 percent of the 80 students who signed up for the package were accepted into one of the eight specialized high schools. Those who are not accepted receive a one-month compensation course to prepare for next year. Meanwhile, Khan’s also offers help for them to get into other selective public schools such as Bard College High School Early College or Midwood High School.

Khan’s Tutorial has begun to advertise in more low-income communities which historically have a low number of students in specialized high schools. In March, Khan’s launched a 12-week SAT prep program in partnership with the Bedford Central Presbyterian Church in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn at about half price.

When asked about options for students whose families cannot afford even the discounted rate, Khan said there is a free city-run program for eligible students. New York Specialized High School Institute, a 22-month test prep program, is available for 6th and 7th graders who receive free lunch, have good grades and attendance records. They also need to have at least average on state math and English exams.

For the ambitious Baidya, getting into Stuyvesant is just the beginning of his academic journey.

“I want to be an architect,” Baidya said, adding that his number one college choice is Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He said he plans to take advantage of Stuyvesant’s participation in the Youth in Engineering and Science (YES) Summer Research Program and MIT Summer Research Science Institute.

But his test prep days at Khan’s aren’t likely to end anytime soon. “I heard the SAT is difficult,” said Baidya. “I will probably be back for it.”