Flushing High School, the city’s oldest, is slated to shut its doors on June 30. The historic school founded in 1875 is set to reopen with a new name and a new staff by next fall.

Cited by the Department of Education for its four-year graduation rate of 60 percent for the past two years compared to the city’s average of 65 percent, Flushing High School is one of the 24 schools scheduled to be closed this year under the new city turnaround plan. Many on the list have been targeted by the state as persistently low-achieving, including Flushing.

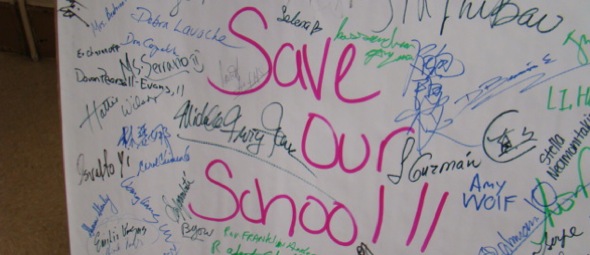

“Nothing is perfect. But that doesn’t mean you shut it down. You fix it,” said Marie Iachetta, a senior at Flushing High, and president of the student council. “If my bicycle is broken, I work on my bicycle until it’s fixed.”

The principal, and half of its teachers are expected to be replaced as part of the city’s response to a federal school turnaround plan. The proposed new principal, Magdalen Radovich, now an assistant principal at Queens Vocational and Technical High School, has already been meeting parents and students at the school, which will be renamed Rupert B. Thomas Academy at Flushing High School Campus, in honor of the former Board of Education member who pushed the city to build a high school in Flushing.

Critics say that Mayor Michael Bloomberg decided to close this group of 24 schools because federal turnaround rules allow half of each school’s teachers to be removed without going through due process. Many believe Bloomberg is using this program to retaliate against the United Federation of Teachers for refusing to back his earlier teacher evaluation plan. The UFT and the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators together filed suit against the city to stop the school closures.

Federal turnaround plans require that all teachers at Flushing must reapply for their positions. Interviews will begin soon. No more than 50 percent of the faculty can be rehired. Those with tenure who are not hired back will be placed in the Absentee Teacher Reserves pool, where they become substitute teachers or perform clerical work.

Meanwhile, their peers in seven other high schools in Queens slated for closing will face the same fate.

Administered by the federal Department of Education’s Office of School Turnaround, the program awards School Improvement Grants to states that adopt the turnaround model. New York State received about $41 million last year. In addition, states are also eligible to receive funding from President Barack Obama’s Race to the Top initiative if they adopt the turnaround model in their schools in the bottom 5 percent.

“We have too many people in the building,” said Albertson. “The students are not getting the attention they deserve.” Most of his classes reach the maximum of 34 students and one of them has more than 40.

Outside of school’s landmark neo-Gothic style building on Northern Boulevard, Katherine Flori, a Flushing alumna and a teacher at Bryant High School, also slated for closing, passed out flyers at a recent public hearing with information on a citywide rally against school closures. She said it is not fair to blame the teachers.

“The student body is very different from when I went here,” said Flori, class of 1961. “Many of them don’t speak English and it takes a long time for them to catch up.” More than 20 percent of Flushing’s students are designated English Language Learners by the city’s Department of Education.

“The student body is very different from when I went here,” said Flori, class of 1961. “Many of them don’t speak English and it takes a long time for them to catch up.” More than 20 percent of Flushing’s students are designated English Language Learners by the city’s Department of Education.

The Flushing that Flori grew up in was a very different neighborhood, where most residents were white and of Italian, Irish and Jewish descent. Today Flushing is home to the largest Asian communities in New York City with more than 40 percent of its residents being of Chinese or Korean descent. More than half of Flushing’s students are Hispanic and 20 percent are black. Another 20 percent are Asian, most of them recent immigrants.

Ziyi Yu, a 10th grader who arrived from Shenyang, China, more than two years ago, said the teachers at Flushing High School are competent, but some of the students cause problems.

“They smoke and skip school,” said Yu. “Some of them bully the Asian students. For me, I just try to stay away from them and stay out of trouble.”

Yu said he has mixed feelings about the closing but hopes there will be positive changes.

“We need more security guards,” he added. “Maybe a new school will be stricter.”

Yu’s mother, Jing-yan Zhang, said she was horrified when she found out her son was assigned to Flushing High School.

“My friends told me that when a child enters Flushing High School, his future is over,” said Zhang. “Many Chinese families moved to Bayside or other areas so their children don’t have to go to this school.”

But Zhang said it is difficult for her family to move because both her husband and she work in Flushing and speak little English. They also cannot afford higher rent elsewhere.

Jenny Chen, who teaches in the Chinese bi-lingual program, said the student population has changed over the years, especially after the Department of Education closed high schools in nearby areas and started sending their students to Flushing.

“Our school receives federal funding so we don’t get to choose what students we have,” said Chen. “If they keep closing down schools, like Jamaica High School, where do those low-performing students go? They come here.”

But Chen said a large school like Flushing High School offers something that small schools don’t.

“If they want to take Advanced Placement classes, they come here,” said Chen.

Chen, who is tenured, she said she will reapply for her position and try to stay with her students until the last minute.

“I cannot abandon my kids,” said Chen. “They need my help and I love them.”

For Flushing’s students, the fight is over and many feel defeated.

Iachetta, an aspiring forensic scientists who chose Flushing as her number one school four years ago because of its Thurgood Marshall Law Academy, said she was speechless when she learned the school’s fate.

“My plan is to just make the best out of what is left of my senior year,” said Iachetta, who will be attending John Jay College of Criminal Justice in the fall. “And create memories that no one, not even the DOE, can change.”

FHS became a dumping ground when other schools closed. It is

being punished for a student population in which 50% have ESL

difficulties and a small percentage have a lmited desire to learn

for whatever reason. When I attended this school oh so many years

ago it had some excellent teachers and some who might be considered

for another line of work…it seems strange at this point in time

to say good bye to a school which is only as good as you can make it.

To those who considered FHS a school of last choice because they did not qualify for Bronx Science, et al…did FHS provide you with a solid foundation for the future? Did you work hard for it or was it handed to you?

As the final bell tolls at FHS hold your head up high…