Toni Ceasar, was never tested for possible learning disabilities as a child. She remembers struggling with reading as a child. She was clearly smart; her IQ was 134. But she had a lot of trouble memorizing words, and then recalling them when she had to use them in essays.

When her two sons were diagnosed as third and fifth graders with dyslexia–a neurological disorder that makes it hard to decode written words–she finally recognized herself as having that disorder. She was inspired to get training in a specific reading method that she saw was of benefit to her sons.

What she learned was that every child experiences the disorder differently. The stereotypical assumption is that dyslexic kids see letters backwards, which may be true for some, but not for all. Dyslexics see what a normal person sees, but they decode the text differently. Some read the words correctly, some get frequent headaches when they read. Those with severe dyslexia see the words “marching off the page.” This can impact the way children process language in general. Some have difficulties understanding the sounds within words, some can’t remember words, even in a short time period. Others have trouble quickly processing verbal instructions.

Today, Ceasar is certified as a reading specialist trained in specific techniques to identify and tutor children with dyslexia, positions and skills that a bill in Albany hopes to encourage throughout the state’s public school systems.

Dyslexia is gradually gaining recognition among public school officials as a disorder that can be treated and minimized with specific early intervention and systematic, individualized tutoring. However, experts say that with fewer trained teachers, tighter school budgets, and overcrowded classrooms, tackling dyslexia may be difficult, but not impossible.

The pending bill in New York State legislature aims to require more teachers and administrators be trained to diagnose dyslexia and other learning disorders, and receive training in various methods to manage it.

Assemblyperson Jo Anne Simon, the main sponsor of the dyslexia bill, said she has great hope that the bill will pass, with the help of active parents in D.C.’s Decoding Dyslexia support group.

“There have been bills passed through the country with regards to identifying students with dyslexia and providing intervention and additional training,” she said.

States like Texas and Mississippi have dyslexia bills that require schools to screen their elementary school students and either encourage or require teacher training.

Approximately 10 to 15 percent of American public school children have dyslexia, according to Dyslexia Research Institute, a resource organization. Experts believe many teachers misinterpret their problem as a simple reading problem, since many elementary school students are learning to read.

“Assessment data needs to be carefully analyzed and instruction has to be adapted to their exact needs. If students can become successful at reading early on–before the end of grade three–they will be much more successful later on in school,” said Brandi Noll, an assistant literary professor at Ashland University in an email.

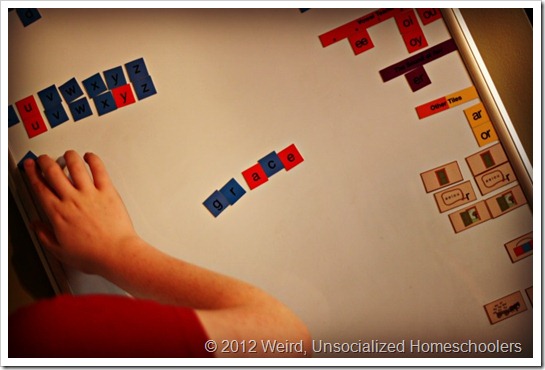

One March morning at a private elementary school in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, several students strolled into Ceasar’s room throughout the day in pairs or individually for an additional 45-minute reading instruction using a reading method. After noon, two students at The Sterling School sat across from their teacher on a wooden bench in a small room to learn words and sounds for their upcoming spelling exams.

Ceasar first reviewed words like toy, duck and picture with them. The fourth grade boy, who had curly brown hair, and the sixth grade girl, who wore glasses and had side bangs, answered as best they could. Ceasar pulled out a small dry erase board from the cabinet behind her and wrote the letter “r” with an erasable marker. The boy sounded out “ar” and then Ceasar asked the girl to place an “o” in front of the “r.” She replied hesitantly “Or.”

Ceasar moved on to the next sound, “oy.” The boy asked if the words were together. She asked the children to sound it out. The boy used his finger to “write” the word on the table. The boy and Caesar said “O” in unison and then he repeated the letter.

“Consonant?” Ceasar said, waiting for the boy to say “y.”

“E,” replied the boy.

“Says?” Ceasar said, waiting again for the boy to say the sound “oy.”

There was a short silence. The boy struggled to search for the meaning of the word.

“Oy,” the boy said.

This method is called the Orton-Gillingham approach, a reading strategy intended to help children with dyslexia improve their reading skills with smaller groups rather than larger groups. This approach employs most of the five senses to teach students how to pronounce syllables, write, and spell words by deconstructing the structure of words bit by bit, using typically six or seven different types of syllables. Students must master each syllable before moving on to the next.

Founded in 1999 by certified Orton-Gillingham trained reading specialist Ruth Arberman, the Sterling School is one of the 178 New York State private schools that serves 24 second through sixth graders with learning disabilities, according to Private School Review, an education review website.

The total number of public schools that serve dyslexic kids is difficult to calculate since dyslexia isn’t isolated from general special education data, but according to the SchoolDigger, another education review website, there are 14 special education public schools in the city under District 75. The NYC Board of Education didn’t respond to a request for the number of city trained specialists in dyslexia.

Reading Reform Foundation, an organization that offers a training program based on the Orton-Gillingham or similar approaches, works with 1,344 public elementary school teachers and serves over 33,320 students. It charges principals $3,000 per classroom and another $3,000 (includes books and materials for lessons) for a consultant to work with teachers during the school year.

“We’re in classrooms that have English Language Learners, kids with problems, etc., but those classrooms reflect lots of problems today in New York,” said Sandra Rose, founder of the organization that partners with Manhattanville College.

She said that her program’s success is based on explaining English spelling and meaning efficiently through the use of bodily senses.

“One, it’s multisensory, nobody teaches that way,” she said, “And multisensory means teaching spelling first. You don’t put kids into books, you have them writing the words, sounding them out, and examining the words of spelling.”

Many dyslexic students have to work extra hard to learn the basics of spelling and enunciating the words. They might recognize simple words, but they forget how to pronounce them, which is frustrating. This may lead to poor social skills and low self-esteem, since many dyslexic children have trouble reading social cues and finding the right words when conversing with others, according to LD Online, an education site for a Washington D.C public television station.

There is no cure for dyslexia and it cannot be outgrown. Dyslexia falls into the broad category of Specific Learning Disabilities, a section of special education that includes Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, autism, etc. Advocates for dyslexic children argue that children with all these various disorders are often grouped together in classrooms and taught using the same techniques, which often aren’t effective across the spectrum.

Dyslexic students who receive instruction in general education classes can run the risk of falling behind if their specific attention go unaddressed although that doesn’t mean they are incapable of performing well in other tasks.Experts have noted these students who have high IQs like Ceasar can soar in school with the help of learning methods such as Orton-Gillingham, Spalding, Wilson Reading and Lindamood Bell.

Lindamood Bell requires trained reading specialists to use lettered blocks then remove it from the students’ sight, and allow them to visualize the images of the letters and then the teacher would ask them about a letter that they have pictured in that word, according to Sonia Rapaport, Associate Center Director of Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes.

The Spalding method, similar to Orton-Gillingham, uses general instruction rather individual. Teachers present the class a list of letters, ask them to recite the sound of the letters then dictate the letters while the students repeat it and write it down. Educators use the Spalding Clock, a method that helps students write the letters of the alphabet based on its formation: circle or lines, according to Your Kids OT, an occupational therapy website.

Wilson Reading, similar to Spalding, is geared mostly towards dyslexic adults. In school classrooms, kids recite the sound of the letters and then when reciting words teachers present to them, they finger tap as they enunciate each letter, according to Learning Disabilities Worldwide, a learning disability organization. Afterwards, the students create words using the color-coded interactive board and determine whether the letters are closed or opened.

As the dyslexia bill mentioned, many education experts believe any of these methods would help dyslexic students to thrive in school.

Orton-Gillingham, designed in the 1920s by neuropsychiatrist Samuel Orton and teacher and author, Anna Gillingham, is the foundational program for most reading programs. Orton first studied adult damaged brains and discovered the root of the learning disability lay in the “failure of the left side of the brain to dominate over the right in the process of reading,” which makes processing text more difficult since it’s not adjusted to it,” according to Dyslexia Reading Well, a dyslexia website.

Some argue that dyslexic kids need long-term instruction rather than short-term techniques.

“You can’t expect that when a kid is dyslexic that you’re going to put a 12-week or 20- week program and think that everything’s going to be fine,” said Mary Beth Crosby Carroll, a Brooklyn elementary school teacher. “Kids need a couple of years of solid instruction.”

Others, like Noll, a literary professor, said in an email that it does help students read individual words, but it “has not been proven in unbiased studies to be successful in actually helping students to be better at real reading and writing.”

Assemblyperson Simon did not know what the costs will be if this approach were to be scaled up into public schools, although she said training principals in something like Orton-Gillingham could ensure that teachers who are exposed to it can identify the students’ reading problems.

Neurologists, researchers and specialists are trying to understand why reading approaches tend to help. Now, their focus is on the difference between the brain of someone with a learning disorder and a person’s normal brain, how brain wiring becomes disrupted and “the role of hormones and neurotransmitters,” chemicals that transmit signals from one nerve cell to another, LD Online reported.

In the last 10 years, researchers have been using two safe imaging tests, Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetoencephalography technology, which allow them to view the brain and understand a dyslexic person’s brain.

“Both methods allow you to investigate what happens when a person is behaving — performing a specific task,” said Barbara M. Calhoun, a senior research scientist at Scientific Learning Corporation, a research site in an email, “One challenge is to determine the appropriate task(s) that will isolate the behavior of interest or specific aspects of it.”

At The Sterling School, Ceasar adjusts her methods according to what kind of learners her students are either by watching, listening or hands-on learning.

Ceasar wrote on her small white board the sound, “oy.” The girl who wore glasses continued to struggle with it. She wasn’t sure whether “oy” was in the middle or end of a word. Ceasar asked the boy what the “key word” was, referring to the sound “oy.”

“Olive oil,” the boy said slowly.

“Can you help her out with the key word?” Ceasar asked patiently.

“Oh yeah, um, at the end, yeah, at the end.”

Ceasar told the boy to tell his classmate the “key word.” He didn’t understand what she meant by keyword. The boy repeated olive oil. So Ceasar decided to write on her small board she was carrying “oy.” The young boy didn’t know what it was and then quickly remembered and said “oy.”

Ceasar asked the two kids what words end in”oy?” The clock was ticking. Eight seconds passed by without a response. Then the boy said, “I don’t know.” Then the girl said, “Yeah.”

“I do,” Ceasar said, in a loud voice, “toy.”

The girl was astounded by the answer because she forgot. Ceasar told the kids to write it three times and said “oy.” They wrote the word out with their fingers on the table and said “oy.” (This technique was used to help the students remember the word “toy” which ends in “oy”.)

“And where does it come?” Ceasar asked.

“At the end of the word,” the boy said.

“All right,” Ceasar said happily.

Please sign this bill into law. Supporty child and many others who have this widely undiagnosed condition.

Very informative post.Really thank you! Awesome. defdcaakceeadbkd

Hi, Neat post. There’s a problem with your site in internet explorer, would test this IE still is the market leader and a good portion of people will miss your excellent writing because of this problem. ecdeeggckcaaeage

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You have ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye gecaebdekaadcbcb