Keeping track of New York City’s schoolchildren when all the buildings are closed is still a work in progress. Now that instruction is all online, each school is left to redefine not only what attendance means, but why it’s central to ensuring that their students are learning.

Art by: Adrienne Sacks for School-Stories.org

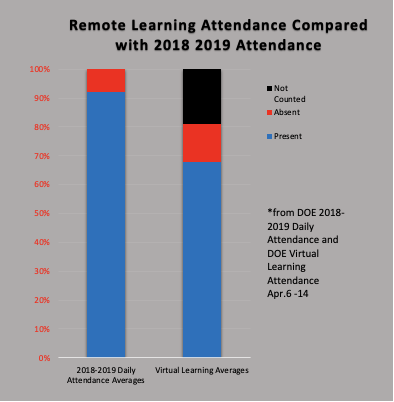

On Mar. 23, schools transitioned to virtual learning making attendance difficult to track. Compared to last year’s rates, attendance is about 8 percent lower during virtual learning according to the Department of Education. However, about 209,000 students have not yet been counted. With classes now online, the DOE has left it to the schools to figure out their own methods of measuring attendance. As a result, there is little consistency in how the city’s schools track attendance.

City-wide data was not recorded until Apr. 6, nearly three weeks after the shutdown. On top of that, almost one-fifth of the city’s schools, or about 350 schools, are not included in the city wide numbers since they have yet to report their rates.

By May 14, the preliminary data provided by the DOE only includes daily records from Apr. 6 through Apr. 14. The report showed that about 84 percent of students attended virtual school. Grades 3 through 5 had the highest rate at about 88 percent, while grades 9 through 12 had the lowest, at about 77 percent. Pre-kindergarten through second grade and grades 6 through 8 both had an 86 percent attendance rate.

Schools submit attendance rates through the Student Interaction Tracker on STARS Classroom. “An easily accessible and familiar online system that schools use during normal school operation, but is not used for attendance,” the DOE said in a statement. The DOE advised schools to indicate on STARS which students have or have not interacted in a day.

All schools may use the same program, but with about 1,800 schools in New York City, schools have adopted diverse methods of defining and tracking interaction.

At Queens High School for Information, Research, and Technology in Queens, students mark themselves present by checking their name off on the school’s website. As of May 8, the school has a 67 percent attendance rate, about 20 percent lower than before the pandemic.

William E. Grady Career and Technical Education High School in Brooklyn tracks attendance through a software. By logging in at the start of classes, students receive a “stamp” marking them present for the day. According to Principal Tarah Montalbano, the school’s attendance rate went from 84 percent last year to 72 percent during virtual learning.

At Khalil Gibran International Academy in Brooklyn, students are expected to attend one virtual class a day according to Principal Carl Manalo. The school had an 83 percent rate and now has a 60 percent rate.

To be marked present at Pathways In Technology Early College High School in Brooklyn, where attendance dropped from 91 percent last year to 80 percent as of May 8, students engage with their teachers with a call, email, or video chat once a day according to Principal Rashid Ferrod Davis.

But behind these numbers, factors like a student’s access to technology, on family support, on teacher’s individual approaches, on prior attendance problems, on how easily the subject translates to an online format, and the list goes on, affect a student’s attendance.

Before the pandemic that prompted the shutdown, attendance seemed simpler to record. Is the student in the classroom, or aren’t they? According to the Standards for Attendance Programs distributed by the DOE, daily attendance was taken by teachers in the classrooms and then imputed to Automate the Schools, an administrative system used by all schools in the city.

Now that teachers are not in physical classrooms, the current attendance system, a spokesperson for the DOE, said, “cannot be considered attendance in the traditional sense.” Still, “it helps us understand who is and isn’t interacting daily, and is data we’re using to support students and prevent learning loss,” said Miranda Barbot, spokeswoman for the DOE, in a statement. “This allows us to push for the best learning experience possible and prioritize meaningful engagement, frequent learning opportunities, and continued support from staff.”

So why does attendance, the traditional version, or the remote version, matter anyway? There are two parts to attendance, according to Gary Miron, a professor at Western Michigan University who specializes in evaluating education. First, attendance is a financial tool used to keep track of where children are. Through Fair Student Funding, New York City schools receive money on a per-student based algorithm that factors in age and need level. Already, with pandemic-related budget cuts, the fund was cut by $100 million — the most significant reduction to the DOE’s budget so far.

The other component of attendance deals with engagement and gauging if a child is present, not just physically, but is learning. This part of attendance is the most elusive to track during remote learning, and even before the transition.

University of Washington’s Center for Reinventing Public Education has tracked how districts across the nation approach attendance. Researchers identify multiple dimensions of attendance, such as whether teachers provide feedback to student work or host check-ins. This method may give a more accurate picture of the engagement component of attendance and factors in components the DOE’s preliminary data does not.

The researchers, according to Alice Opalka, a research analyst at the Center, look to see if teachers are setting expectations and monitoring their students in ways like making calls home. “We are not assessing engagement, but also the quality of engagement,” she said.

In many ways, New York City is ahead of other districts, even if the bar is low. Although New York City’s approach to tracking attendance may be flawed, it has a policy for tracking while many districts do not. Also, New York City offers instruction for all grade levels and, according to the data gathered by the Center, it provides feedback for all grades but one-third of districts in the study do not.

No matter what aspects are considered, tracking engagement is challenging, according to Miron. Still, data helps make sure that no students fall through the cracks, especially these days where face-to-face contact is rare.

“There’s a lot of young vulnerable children that are left there to learn on their own, or with some minor parent involvement, but these are small children,” said Miron. “What they really need is structured teaching time and an environment where they are seen and heard. That is so critical.”

Miron believes that New York City has a good chance of effectively teaching online since class sizes are relatively small, and because most teachers already had an established relationship with their students. Any way teachers can make students feel “seen and heard” through the screen, he said, will make students more engaged.