High school junior Kastia Colon takes a deep sigh as she lines up for the daily weapons scanner at the former John Jay High School building in Brooklyn. A quiet teenager known for her gentle demeanor, Colon learned long ago that if she wanted to make it to first period on time, she’d have to make a mental note of any coins, keys, or bobby pins that may set off the NYPD metal detector.

About a year ago, Colon added the ritual of taking off her black-rimmed glasses as well. The memory of her Park Slope Collegiate schoolmate Noah Phillpotts is never far from her mind.

Last year, Phillpotts, a Collegiate senior, was handcuffed and forced to the ground by NYPD school safety officers who demanded he remove his glasses. The metal pin he had stuck in his broken glasses to hold them in place had set off the scanner. Phillpotts refused to take them off. Officers restrained the 17-year-old and issued a summons for disorderly conduct.

The teenager was able to get the charges dropped. He since graduated and is now in the middle of a federal civil rights lawsuit against the city and the NYPD.

Philpotts’ reaction against the indignities of the high school scanner had been simmering for some time. His case triggered a year of parent and student-led petitions, protests, and class discussions about discipline, discriminatory placement of scanners, policing, and race relations in school.

“When I first came to this school I thought [the metal detector] would be a one time thing,” said 16-year-old junior Jamal St. Rose. On the one hand he thinks the scanners can provide security, but on the other, he believes if safety officers trusted students to begin with, then there wouldn’t be any fear or suspicion.

St. Rose is one of about 15 students in a growing movement that has now taken a more expressive turn in the shape of a school mural.

On the fourth floor of John Jay Educational Campus that Park Slope Collegiate calls home, Kastia and a few of her fellow classmates sat hunched over the 100-year-old school’s white walls on a recent Sunday, carefully painting tiny figures pushing a metal detector off a cliff. A student wrote the words “Poof!” in black paint. Another student outlined a banner with the words “Unity in Diversity.”

Colon, St. Rose, and fellow middle school and high school peers are among a group of students at Park Slope Collegiate in Brooklyn who have been working for a year designing this protest mural. Overseen by a small group of city schoolteachers and staff members at IntegrateNYC4Me, a grassroots advocacy group, this self-dubbed “task force” has been meeting on weekends to paint and plan a public forum coinciding with its unveiling in May.

Students hope to spark conversation about how symbols of security and criminality have come to define a public school system marked by segregation. They plan to not only rock the halls of their school and other schools across the city, but also to influence policy makers at city school headquarters.

“If the mural is how I picture it in my head, it’s going to be big. It represents so much to each of us and other schools,” said Colon. “But we don’t want it to just represent our school, it has to be so big that it inspires other schools and creates a domino effect.”

Collegiate principal Jill Bloomberg has been pushing to remove the scanner since she first arrived to head her school a little over a decade ago. Four other schools in the building, including Millennium High School, the Secondary School for Journalism, the Secondary School for Law, and an Alternative Learning Center, are also required to pass through the weapons scanner. But only Park Slope Collegiate students have staged a public protest, so far.

Known for its Town Hall meetings, in-classroom debates on social justice issues, and parent-teacher circles on race relations in school, Collegiate has never shied away from contentious issues that plague New York City’s public school system, the most segregated in the country.

“I really believe reform can only happen if something big happens,” said Kastia during one recent social studies class debate.

The debate prompt, “do you think a tragedy is necessary in order for reform to occur?” glowed on the smart board screen in the front of class as students went through different real life scenarios to depict how change occurs. Eric Garner and the Black Lives Matters movement were brought up as examples. Colon sat in her seat quietly stewing, because she knew they had a real life example within their school walls.

The mural plans has been brewing for over a year. During last year’s school protest in response to the Philpotts incident, Kastia joined student council friends Theola Carbon and Feyisola Oduyebo, both 17, as they designed t-shirts that read “I Love John Jay, Not Racism.” Students and faculty all wore the t-shirts as they protested policing in schools and called for an elimination of the metal detectors at the school claiming that they make students feel like criminals.

Students have also joined the effort to diversify Collegiate, which is currently majority black and Hispanic, in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood.

Metal detectors expanded into widespread school use after a fatal shooting at Thomas Jefferson High School in 1992. Juvenile violence and gun crime reached a peak a few years later and has been declining ever since. Even so, a recent ProPublica and WNYC investigation found that more than 100,000 NYC schoolchildren are still subject to airport-style security every day. The same report found more than 236 schools have metal detectors at their entrances and that few weapons are confiscated as a result of the security measures.

According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, 82 percent of children attending high schools with permanent metal detectors were black or Hispanic, compared to the 71 percent citywide average.

“Students at Park Slope Collegiate see the way [scanners] criminalize them and they begin to see the correlation to race,” said IntegrateNYC4Me Founder Sarah Camiscoli. “Metal detectors maintain the stereotype that black and Latino youth need to be scanned.”

Camiscoli and PSC parent Melissa Moskowitz have been an integral part in bringing IntegrateNYC4Me and the mural project to the school.

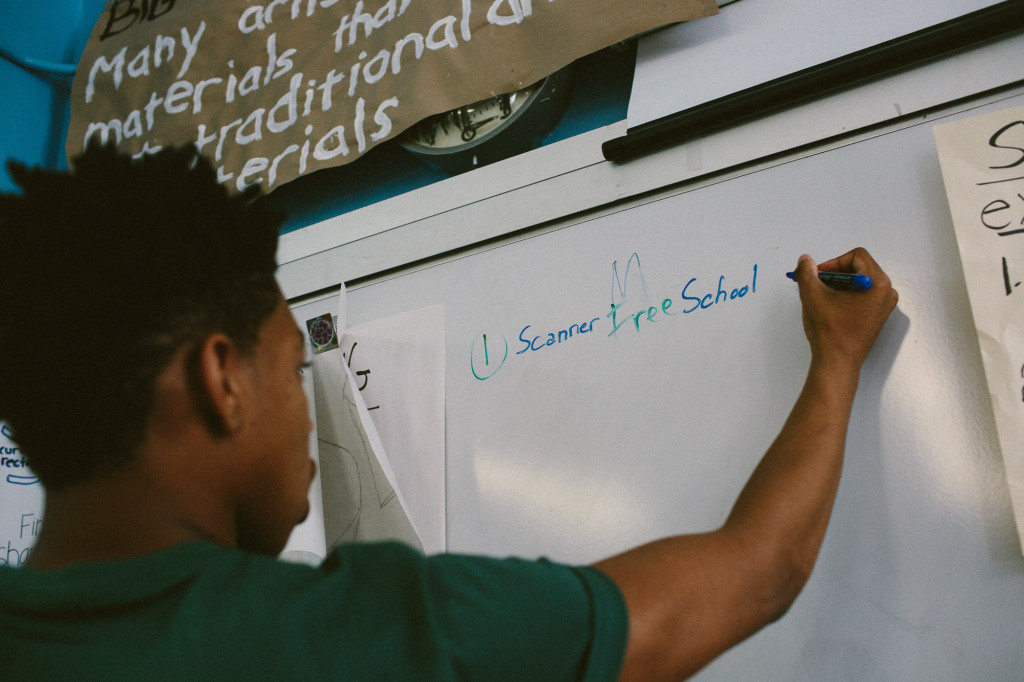

Camiscoli, a teacher at Urban Assembly Bronx Academy of Letters, helped her own students complete a mural on integration, a project that grew into IntegrateNYC4Me, a citywide grassroots advocacy group.

At the first official painting meeting one recent Sunday afternoon, Camiscoli and her group of students had access to an empty and scanner free John Jay building to discuss plans for their public forum. In a circle, the group deliberated plans to open up the event to other city schools such as Brooklyn Technical High School, which is home to a growing #BlackinBrooklynTech movement in response to what students describe as a hostile environment towards black students.

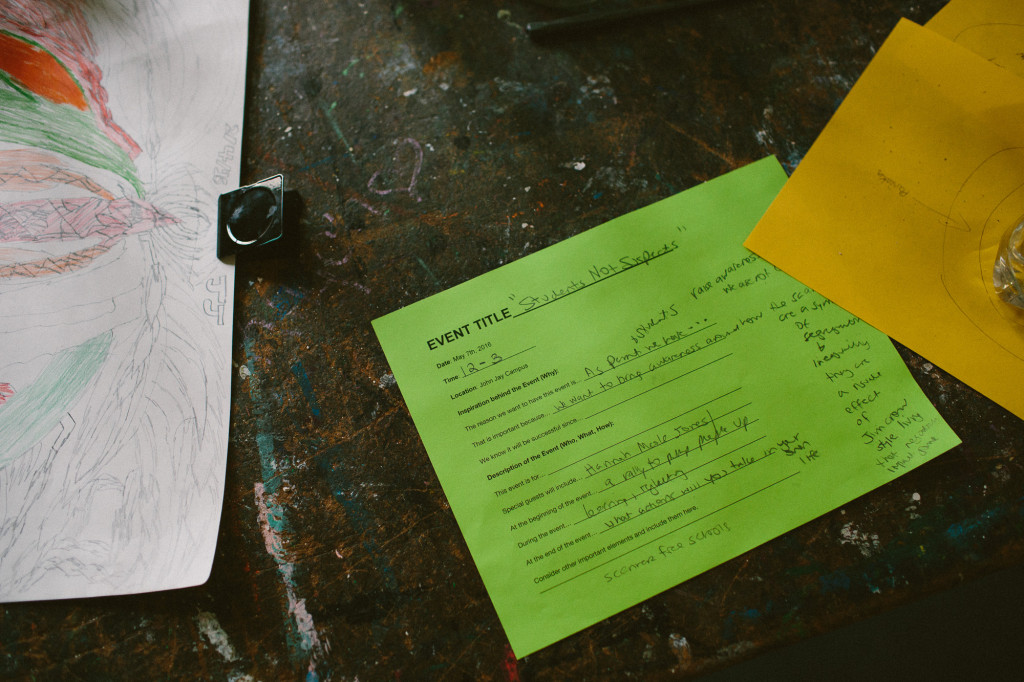

Collegiate senior Feyisola Oduyebo, 17, or “Fey” as she is affectionately referred to, paired up with Sarah to workshop titles for the event they plan to host in May.

Titles ranged from “The Fey Show, to “Student Takeover” to “No Scan Zone.” The group finally settled on “Students Not Suspects.”

Camiscoli asked Fey to remind the rest of the students why they were there to paint the mural. Using her iPhone, Fey cited an article from the Los Angeles Times explaining how scanners are put in schools that are predominately black and Hispanic.

Fey has frequently accompanied the adult leaders to citywide events. At a recent meeting on diversity with Brooklyn Councilman Brad Lander, Fey read from an essay she had written about her experience in New York City schools in the hopes of convincing the councilman of removing the scanners:

“We believe that students of all races and ethnicities should not have to feel like criminals when they come to school,” wrote Fey. “We should be able to walk into our school freely and not have the stereotypical fear that the next person is here to harm me.”

When Fey was a freshman, she remembered being shocked by the metal detector. She worries about her younger sister Lola, a freshman at Collegiate, and other underclassmen, that will become equally desensitized to its presence.

With graduation in June and the mural set to be finished in May, Fey has high hopes that by the time she visits PSC campus next year as a college freshman, the infamous metal detector will be gone.

For more photos, click here.