After years of non-compliance with federal laws protecting the rights of students with disabilities, the city has set its sights higher with school physical accessibility targets for 2024. But the pandemic has disrupted its plans, and our age of remote learning has raised different challenges to accessibility.

Less than half of the New York City’s education buildings are fully accessible to students and families with physical disabilities. The most recent data available shows that only 44 percent of the 645 buildings in the Department of Education’s database are fully accessible.

An investigation into these numbers by Covering Education reveals the DOE’s buildings are more inaccessible than they appear. First, the city has more than 1,000 school buildings that house over 1,800 schools, according to the accessibility coordinator William Herrera, who is responsible for checking that school buildings are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

At least 25 buildings rated by the DOE as of February 2020 were found to be so inaccessible that they don’t even appear in the city’s publicly available database. “We don’t want any non-accessible ratings on this list,” Herrera said, adding that its purpose was to help students, parents and school officials find programs that they can use.

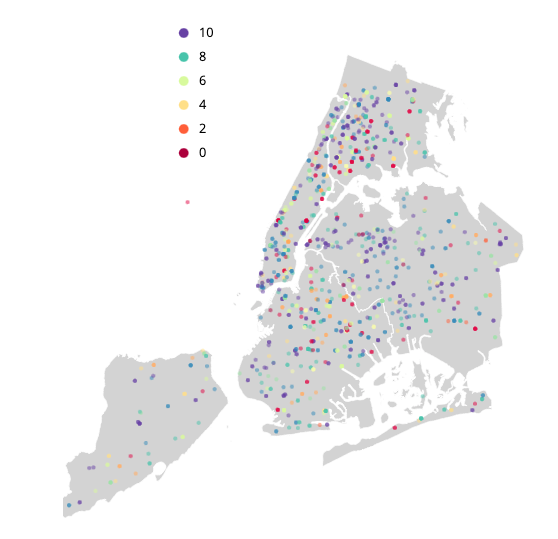

The building ratings focus on physical accessibility. Ratings range from 0-10, with 0 meaning schools are completely inaccessible while all other numbers denote different levels of access, according to the Department of Education’s website. Ratings of 9 and 10 are considered to be fully accessible schools, which generally means that the school building is newer or was upgraded after 1992, the year the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed.

The current database lists ratings for buildings, not for individual schools. Under the Bloomberg administration, larger schools were broken up into smaller ones, and it is not uncommon in New York City to have multiple schools co-locate and share the same building. Nevertheless, access to bathrooms or entrances may differ between schools in the same building, which would not be reflected in the database as it currently stands. Herrera hopes that the next iteration of the database will list ratings for schools.

In 2018, Advocates for Children found that only one in five New York City schools were accessible. But the database has expanded since then; since new buildings are surveyed each year, it can be difficult to draw conclusions about annual progress.

Herrera is part of a six person team at the Department of Education that pound the pavement to inspect buildings. “It doesn’t allow us to deploy and do hundreds in a day,” Herrera said. But “it allows us to have firm control over the ratings we’re giving.”

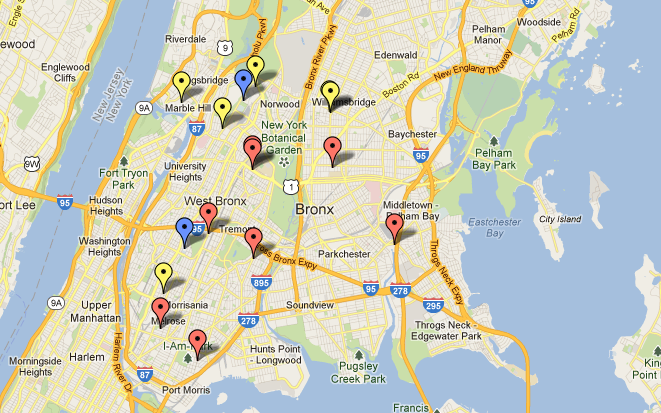

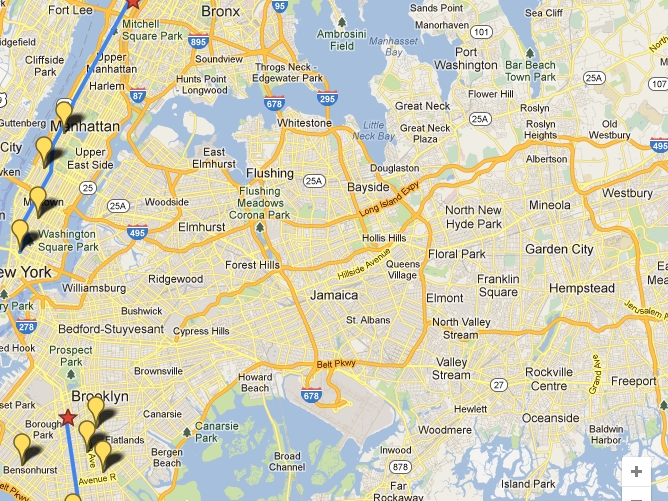

Of the schools that have been rated, Queens has the highest median rating; 55 percent of rated Queens schools scored a 9 or 10. Herrera suspects that this trend is driven by the fact that a lot of schools in Queens were built more recently; an analysis of the rated schools found that more post-1992 buildings feature in Queens than in any other borough, which by law means that they must be compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Read more about historical schools construction here.

By 2024, the department aims to have 33 percent of all buildings within any school district be fully accessible, and 50 percent of all elementary schools to be partially or fully accessible, Herrera said.

But COVID-19 has halted school construction and renovation. While the initial plan was to capitalize on the schools being closed to fast-track renovation, only essential projects have gone forward, making the wait for accessible schools even longer.

Read more about contemporary construction here.

In mid-March, the governor and the mayor closed schools for the remainder of the academic year. The needs of the hour are less to do with physical accessibility and more about providing accommodations for students with auditory, visual and learning disabilities. Betsy DeVos, the education secretary, stated last month that she would not be providing school districts with waivers to sideline U.S. special education law.

Read more about students with disabilities and accommodations in the midst of the pandemic here and here.