For nearly ten years, Jean Arrington walked the streets of New York City trying to track down every school building designed by C. B. J. Snyder. The city’s schools building superintendent from 1891 to 1923, Snyder was credited with building 400 structures and additions all together, about 200 of which are still being used as schools.

Between 2006 and 2016, when people asked the retired English professor if she was in a relationship with anybody, Arrington would reply , “Yes, with a dead architect,” the subject of her research. Illness has since forced her to turn the work over to a team of others.

Snyder’s influence in school design is vast. Even if you didn’t study in New York City, there’s a good chance that Snyder impacted your educational experience — if you used bulletin boards in your school classroom or sat at individual desks placed in aisles, you’ve likely been touched by Snyder’s work, said Dee Laffin, who is now working on the manuscript with Snyder’s great granddaughter, Cindy LaValle and her partner, Michael Janosa.

And his elegant, complex facades and numerous innovations — including the famous interlocking staircases — form part of New York’s rich architectural inheritance, but his legacy poses challenges for architects trying to make his buildings physically accessible. Snyder did not design his schools for children with physical disabilities, a population that was overlooked at the turn of the last century.

As a progressive era architect, Snyder was instead “concerned about immigrants and their success in becoming American citizens,” Laffin said.

Janosa has a background in surveying construction, and discovered Snyder during a gravesite visit over the holidays with LaValle. He was struck by how Snyder’s buildings were both “impressive but also functional, which doesn’t happen as often as we would like.”

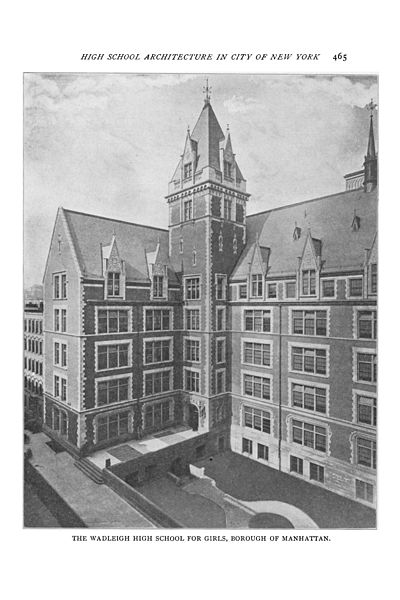

This story is in Laffin’s blood, LaValle said. Laffin’s grandmother, an immigrant, worked as a matron in Wadleigh High School, the first school in Manhattan that Snyder built for girls, while Laffin’s mother and aunts were students. “Their mother was cleaning the toilets and they were learning how to be good people.”

Laffin’s mother and an aunt taught in the New York City school system after; Laffin herself teaches in community college in Suffolk County, a practice she says has antecedents in the “double sessions” that took place in New York City public schools.

When Laffin and Janosa first met, the schools that they’d attended inevitably came up. “Which public school you went to and which borough, for New Yorkers of our vintage at least, is part of our background,” Laffin said.

“Snyder was credited nationally with developing a style called collegiate gothic,” said Jay Shockley,a former Senior Historian at the Landmarks Preservation Commission who has researched and written about Snyder schools. While Snyder buildings might be united in their desire to impress, “he was all over the map style-wise,” Shockley said, pointing to art deco and Georgian revival influences in his work.

When Shockley was assigned to research what became his favorite assignment, Stuyvesant High School, he was surprised to discover secessionist architecture from Vienna.

Snyder was criticized for the perceived extravagance of his designs, but he was able to demonstrate that his aesthetics weren’t breaking the bank, LaValle said.

Snyder’s constant innovation can be attributed to the changing constraints of the time. His shift from steel to masonry coincides with the construction of New York City bridges, said Bruce Nelligan of Nelligan White Architects.

He was also particularly concerned with fire safety as a son of Saratoga Springs, where buildings “would go in flames like a tinderbox,” Janosa said. Snyder wanted his schools to be able to be evacuated within three minutes and built a system of interlocking staircases to facilitate egress in the case of a fire.

The sheer number of Snyder buildings means that sometimes the Landmarks Preservation Commissioners, who were appointed by the mayor, rolled their eyes and asked, “Well, how many C. B. J. Snyders do you want to designate?” But to Shockley, that’s the wrong question to ask. “Why should the Upper West get one but the Lower East Side not get one?”

Arrington initially fell in love with Snyder’s architecture, but it is the passion of the people she has met along the way that kept her writing, researching and walking for the better part of a decade. “Do you feel strongly about your elementary school?” Arrington asked. “I think everybody does.”