Pooja Bhaskar is only in her first year of teaching but already she has had to fight for her students and her school.

The 9th grade Living Environments teacher passionately defended Bread & Roses Integrated Arts High School during a Feb. 13 hearing on a proposal to phase out the school.

But the Department of Education’s Panel for Educational Policy voted in March in favor of the phase out, meaning no new students can be admitted and the school will lose a grade each year until closing completely in 2015. A new district secondary school is opening in its place.

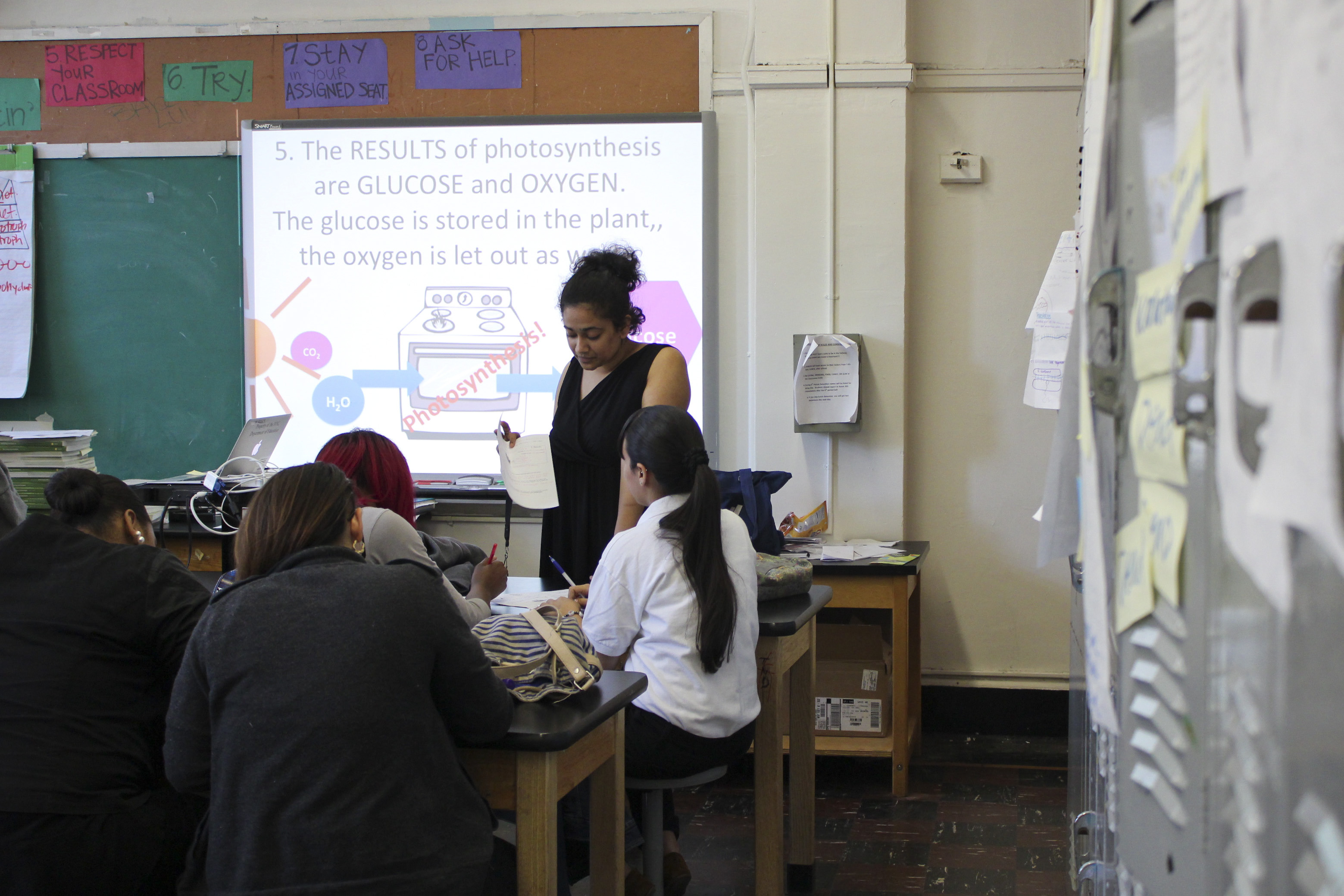

Now, Bhaskar’s position at the school seems shaky. “I was the most recently hired science teacher,” she said, in her second-floor classroom, surrounded by brightly colored diagrams and posters on science topics such as sexual reproduction and mutated butterfly DNA. “I don’t know for sure yet but I feel pretty confident that I won’t be able to stay here, and nobody has said anything to make me feel otherwise.”

If she does have to leave, it will not be an easy transition. “I’m really attached to my students,” she said. “I would’ve loved to see my students become sophomores, juniors and then graduate.” Even if she were at the school next year, she probably would not be able to see that anyway since a lot of her students are applying to transfer out.

“You lose a community you worked hard to build,” she said, adding that she does not think the practice of closing and phasing out schools is effective. “It hurts the community, hurts teachers, hurts students, and it doesn’t solve the problem of New York City schools underperforming.”

Bhaskar, a vivacious 25-year-old with a booming voice and a catchy sense of humor, is a member of the New York City Teaching Fellows program. The program subsidizes her graduate school studies at Brooklyn College while allowing her to teach full time under a special license after an intensive summer training course. She juggles teaching in the day with going to her own classes at night. Depending on what classes she takes, lessons can be once or twice a week. She is on track to graduate next year, and after that she will take a test to get a regular teaching license.

Although science was not her primary passion growing up in California and in college at Reed College in Oregon, it is increasingly becoming one. “I really like being able to come up with ways to simplify challenging concepts,” she said. “Science teaches us everything about the world. It teaches us to be curious and think critically and base conclusions on evidence.”

Teaching as a whole is clearly something she cares about. “It’s what can close a lot of the inequality that we have in societies,” she said. “Teachers have the power to really show students what they’re capable of and build some of their self-awareness.

“There’s never a boring day. There’s always things I can reflect on and do better. I feel that there’s a lot of room to grow in teaching.”

Bhaskar feels that the school closure movement undermines the very values she tries to impart to her students. “We try really hard to show students that you have to work hard and you can move towards anything,” she said. But with school closings, “It teaches our students that when you have an issue or something’s not working, instead of trying to put more resources and effort into fixing it, you should just make it go away.

In a way, being forced to leave Bread & Roses will give Bhaskar the chance to see other public schools in the city. It is, after all, only her first year on the job. She has been interviewing elsewhere while she waits for news, and admitted that she is “curious to find out what other schools are like.” But she will miss the connections she has built with her students here. “I’m very sad, that the school is phasing out, and I’m very sad that I won’t get to see my students finish high school and graduate.”

Another member of staff who has been very involved in the students’ experience of the phase-out is Sabrina Cochran, 40, the guidance counselor for 9th and 11th graders at Bread & Roses. Students regularly come into her office on the second floor to talk about any trouble they are having at the school. Many came in for advise about their transfer options in March and April.

Cochran has tried not to think about how uncertain her own future is at Bread & Roses. “They might not need two counselors next year because the school is getting smaller,” she said.

Although rumors are swirling that there will be cuts in the number of teachers and staff, they will not know for sure until June. The school will only be able to make staffing decisions for next year after the Department of Education sends them their budget for next year, based on a projected register of the number of students who will remain at the school. “Because of the phase-out you have to keep them by seniority,” explained assistant principal Abdurrahim Ali, who has been at Bread & Roses for seven years. “We can’t keep new teachers even if they’re excellent.”

Ali does not like what he foresees as the effects of the phase-out on the quality of staff and students. “It’s rough,” he said, of seeing some of the teachers looking for jobs and interviewing elsewhere. The open market transfer period for teachers lasts from April 15 to Aug. 7 this year, and teachers can apply for positions in other schools. In terms of students, he said it is usually the good kids who have done well so far and can graduate in the next three years who get picked up by other schools when they try to transfer. “So we lose good students and teachers during the phase-out,” he said. “It’s hard.”

Cuts based on seniority are what worry Cochran, who is the more junior of the school’s two guidance counselors. She started working at the school in 2008, though she moved away in the school year starting 2011 to work at a middle school, returning to Bread & Roses this year. She said wanted to get involved in the school because “It’s just a community school and I’m from the community, so I want to help the kids in the community go to college.”

Over the course of the past year, she has built up relationships with the freshmen and will be sad to see some of them go. “That’s a part of your job, bonding with the students, making sure they’re okay,” she said. “If they have problems they come to me, if they’re not comfortable in their classes they come to me.”

Although some staff said at the school’s phase-out hearing that they feel a clean cut of the school would be better than a drawn-out deterioration, Cochran is happy it will stay open. “I’m glad that they’re not closing it completely and they’re allowing everyone here to graduate,” she said.

Even so, she may not be around to see her current freshmen get to the end. But she is trying not to dwell on that thought.

“I don’t know what’s in store,” she said. “I can’t really stress it until I see what’s the outcome, so I’ll just have to wait and see and hope that I’m able to stay.”