If there were a visible class line in Manhattan, it would stretch across 125th Street, isolating one of the city’s historically impoverished neighborhoods: Harlem. Even though gentrification has crept into the area in recent years, crime and poverty still guard Harlem, preventing generations from breaking free from a cycle of social inequality.

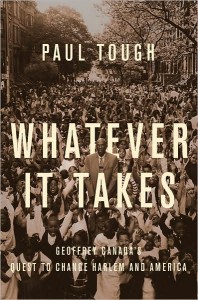

If Geoffrey Canada has his way, however, this cycle will soon end. In 2004, the Bronx-born social activist devised a plan to teach people to move beyond social barriers to future success. To do so, he realized he had to start from the beginning and provide children with new survival skills.

Canada’s plan involved millions of dollars, idealistic promises, and an entire neighborhood’s support. Harlem serves as his laboratory for this social transformation and Paul Tough has become his unofficial biographer.

In Whatever It Takes, Tough followed Canada for almost five years as he attempts to figure out how to reduce the disparity between low-income children who typically are black and Hispanic and middle-class children who usually are white. Canada, who had long been involved with social justice programs, chose central Harlem because the area’s statistics were so startling: More than 60 percent of children live in poverty and many fall below grade level on state tests.

Tough, a former editor at the New York Times Magazine, portrays Canada as a man on a mission to save his community, which was once the epicenter of African-American culture. Tough has impressive access into Canada’s life: He cleverly weaves in details of Canada’s life as he depicts the birth of Canada’s project, the Harlem Children’s Zone and its various programs, such as Baby College and Promise Academy, a charter school. By providing intimate details of Canada’s background — sharing his troubled childhood and struggles as a young black man — Tough is able to address the issue of race without politicizing it.

Tough also weaves in several academic research studies, adding context to Canada’s plan to open a charter school and to create other wrap-around services. The research speaks for itself. Tough introduces how the use of language at home — even the number of words parents speak to their children — significantly affects the development of a child’s skills at an early age.

His reporting is detailed, his research wisely chosen. But Tough often fails to critically analyze the issues he writes about. Perhaps Tough fell into a familiar trap for journalists who are given intimate access to their sources — he seems reluctant to question his sources. For example, Tough doesn’t examine whether determining school success only by using test scores is the best method, even though Canada makes a major decision about Promise Academy, the charter school he opened, based on student test scores.

And Tough mentions in passing that almost a dozen teachers quit after the first principal was fired by Canada, a move that hinted at internal tension at the school. Tough neglected to follow up. It’s possible that Tough wanted to concentrate on the larger picture, but he may have missed out on important details that could give readers more insight into the relationship of social inequality, race and education in the United States.

At the same time, Whatever It Takes makes a strong case that “increasing the educational success rate of children in poverty is essential to the nation’s future.” Four years after writing about Geoffrey Canada and his organization, Promise Academy has been successful enough to grow into two schools and help more underprivileged students in Harlem.