The teacher’s lounge was full, but nobody was lounging.

English teacher Ann Neary sat before an old Dell computer at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, trying to concentrate amidst the hallway clamor of students changing classes. Her keyboard was bookended by her morning Starbucks coffee on one side and her dog-eared copy on the other of The Hudson Review, a popular literature quarterly.

The nine-year veteran teacher dressed in jeans, boots, and a Valentine’s Day t-shirt was preparing a writing lesson on a short story called A Trip to Carfin by Donal McLaughlin for her Advanced Placement English seniors.

Nearby, Neary’s 25-year-old student teacher, Greg Castro, was poring over the short story, looking for examples of setting, and writing them on fluorescent index cards. Teacher to teacher, they discussed important characters and quotes that pop. Suddenly, the Internet crashed. Then the printer broke.

Just before the fourth period bell rang, Neary sent Castro downstairs to the classroom to set up while she scrambled to find a working printer before the bell.

It’s hard enough for a veteran teacher to rally under these circumstances. When a rookie’s first student teaching experience is in a resource-starved school, more than just typical first-year struggles happen. Generally, DeWitt Clinton doesn’t receive many student teachers.This year administrators estimate that they have three or four for its 3,000 students.

Beyond that, Neary, the mentor, had never experienced being mentored herself. Neary had come into teaching through a fast-track certification program nearly ten years ago; Castro through a traditional four-year program at Lehman College.

Despite the current nationwide focus on measuring how well teachers perform after they’re in the classroom, there is only a fledgling discussion about how well they are prepared before they get there. Even less is known about the experiences of student teachers at schools like DeWitt Clinton, which still uses chalkboards, handwritten attendance sheets and paper timecards.

Most classrooms at DeWitt Clinton have no computers and no printers. Teachers share classrooms, carrying their materials in and out of the room each period much like the students who switch classes every 45 minutes.

On paper, DeWitt Clinton is a failing school. One of the last large, comprehensive high schools in the city. Half its population are new to English or have special needs. For the last three years, “the castle on the parkway,” as the school is affectionately known, has received an official “F” on the system’s fairly new annual report cards, a contested legacy of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Last year, Department of Education officials downsized the school, which used to serve over 4,000 students, to make way for two co-located schools to move into the building.

The New York City Department of Education describes student teaching as an opportunity for soon-to-be teachers to gain practical experience “with the guidance of an experienced cooperating teacher.” Traditionally, veteran educators help shape student teachers into first-year teachers, drawing largely on their career experience and shared memories of their own student teaching. But the condition of the school often impacts the student teacher’s experience there. Castro, who is originally from White Plains, said he was aware of the school’s struggling status when he was placed there. And it didn’t worry him.

The Lehman senior has known he wanted to be an educator since high school. Two of his French teachers at White Plains High School told him they expected to see him back at the school as an employee one day. Castro ran with the idea.

“I feel really comfortable in the classroom,” said Castro. During lessons, Castro hesitates to raise his voice over student chatter. But during individual and group work he easily swoops in to ask questions and offer help–and laughter. “I love to engage with students, you’re not just there to fill up a bucket of knowledge,” he said.

After graduating from high school in 2006, Castro enrolled at Lehman College and paid for his tuition out of pocket. Money struggles forced him to go to school on and off for several semesters while he worked to pay for his education. Classroom courses and over 30 hours of classroom observations logged at the beginning of his certification program didn’t prepare him for the challenges he’d meet in his first two weeks on the job.

“I’ve taken all these courses and I understand some things, but when I walked into Mrs. Neary’s class I thought, ‘Thank God I’ve worked with kids before,’” he said.

Castro said his coursework at Lehman lacks realistic training in classroom management, lesson planning and collaborative teaching. “They prepare you for an ideal setting,” he said. “And nothing is ideal.”

For Neary, things were hardly ideal when she started at DeWitt Clinton, either.

In February 2004, Neary, then 49, enrolled in Jump Start, a seven-month joint master’s degree and teacher’s certification program at Manhattanville College in Purchase, New York.

For 25 years she’d worked in the fashion industry as a buyer for companies like Lord and Taylor and for designer Kathryn Conover. Neary bought everything from women’s dresses to sportswear. Co-workers noticed her affinity for teaching during a stint at Brooks Brothers, the menswear company, where she trained new hires straight out of college.

“People used to ask, ‘Why aren’t you a teacher, why aren’t you a teacher?’” said Neary. “I had this thing bubbling in the back of mind. Teacher, teacher, teacher.”

Jump Start students start classes in the spring and continue through the summer. By September, Neary had a teaching license and a full-time job at DeWitt Clinton. When she stood before her first English class, full of freshman remedial English students, she had never taught a class by herself.

Today, she finds herself in the ironic position of teaching a student who is nearing completion of a traditional teacher’s education program. Neary must help Castro understand what to expect in an urban, senior English classroom, while they both learn to manage the delicate relationship between student teacher and mentor.

Neary’s Jump Start experience involved observing a classroom for 30 hours, not teaching in it. She spent her time in urban and suburban schools in New York and Connecticut. When she finally had a chance to watch Laura Payano-Ortiz, a DeWitt graduate, teach English, she knew she wanted the challenge of an urban school.

By her second year, she’d been given a student teacher. Neary says this practice of beginners teaching beginners technically violates the union contract, but she didn’t know that then. That spring, she had a difficult assignment. Neary had been given the “Ramp Up” program. These second semester ninth graders had failed four academic classes and have trouble with truancy. All of these students were put into one classroom and remained there all day. Teachers rotated in and out of the classroom for fear students would leave campus if allowed to switch classes in the hallways on their own.

Neary’s student teacher that year was a graduate student at Columbia University’s Teacher’s College. “I’m having trouble understanding the philosophy and the kids are unruly and she’s here with me,” she remembered.

The New Castle On The Parkway

Castro’s student teaching experience began at the cusp of change in a school that badly needed it.

Santiago Taveras, who served on the former Chancellor Joel Klein’s cabinet as his deputy, was brought in this year as the new principal to try and turn the legendary school around. Years of stagnant progress have plagued the once revered school. But since Taveras stepped in, daily attendance rates have increased by more than 2 percent since last year according to the most recent Quality Review Report.

Twenty-five smart boards have been installed in classrooms since the beginning of the year. Taveras dismantled a school program that lumped all “at-risk” students together on one floor, keeping them segregated from the rest of the student body. He has reinstated school dances, pep rallies and other morale boosting school traditions. Taveras greets students in the morning and in the afternoon, even filming kids trekking through the snow to school during a recent snowstorm.

The school was rated as “developing” on the Quality Review Report, a step up from last year’s rating as “underdeveloped.” Taveras, known as Santi to staff and students, is pushing teachers to attend regular professional development and trying to boost teacher collaboration, such as a common, school-wide grading policy. Changes are happening fast and Taveras said if teachers aren’t moving forward with him, he “will help them find another job.”

Still, the school has suffered a dramatic drop in enrollment—down to 2,746 students this year from 4,158 students last year. This is due in part to two independent schools added to the third floor. The school’s counseling staff is bogged down with caseloads in the hundreds. While all students are eligible for college advising, students enrolled in the Macy Honors Program tend to be the ones targeted for much needed help with college applications.

Despite these woes, Neary thinks that student teachers can learn a lot at DeWitt Clinton. She has mentored several student teachers from Lehman and other colleges during her tenure.

“It’s critical that they spend time with a teacher,” Neary said. “I make my student teachers work. There’s no sitting and watching me work. They have to be engaged with students.”

After each lesson, Neary involves Castro in a reflection of the lesson. She asks him what went well and what didn’t, and solicits his help in making adjustments before the next period begins. Lehman College, Neary said, has responded well to her feedback about student teachers’ shortcomings in the past.

“I have on occasion had some student teachers who have been amazingly ill-equipped,” she said. “I get to talk to their professors and say ‘I think this is where students need to spend some time before the student goes out on their own into the classroom.’”

She also recognizes the shortcomings DeWitt burdens student teachers with.

“We don’t have enough technology,” said Neary.

Elvani Pennil, Director of Field Experiences at Lehman College, manages all school placements for student teachers in the education program there. When Castro met with her, they talked about placing him at DeWitt Clinton or at the Bronx High School of Science, minutes away. Bronx Science, a specialized public school, has earned an “A” on the city’s report card for the last three years. But Castro’s experience working as an advocate counselor for the Department of Youth Community Development at the International School for Liberal Arts (ISLA), a middle school housed in the old Walton High School building, pushed him to take on the challenge. Pennil said students who are placed in a struggling school face unique challenges.

“A placement is only likely to yield success if the student teacher is working with a strong cooperating teacher,” said Pennil. “Teachers who know and love their content and who engage struggling students by providing them with ways to access that content make excellent mentors.”

Neary thinks student teachers are better off working in schools that reflect the realities of the schools they’ll eventually get hired at.

“Bronx Science is supposed to be the gem, but that’s a selective school. It’s not the norm,” she said, defending DeWitt Clinton. Students there must pass the selective high school exam in order to be considered for admission.

“If you’re going to teach, you might as well learn what it’s really like in New York City,” said Neary. “And we have a good school to teach that.”

Castro’s classmates told him that DeWitt Clinton was “all gangs and fights” after learning that he’d opted to teach there over Bronx Science.

To outsiders, the sight of students lined up to go through metal detectors, which are housed in the scanner room in the school’s basement, might reinforce those presumptions. Students must remove their jackets and belts and show their school ID cards. Bags are placed on moving belts and scanned one-by-one, TSA-style. “What’s in there?” the students are frequently asked. Then, they’re required to walk through metal detectors to gain entry to the building. Some students are even searched using a hand wand by a NYPD school safety officer. One morning, a male student was asked to walk through a scanner multiple times. A line of students waiting to get into school extended out the door behind him.

“Nope, you’re buzzing. Take off your jacket,” the officer said and pointed him back around the scanner for a second and third try. This happened well after first period had begun.

Castro was well aware of DeWitt Clinton’s academic struggles when he agreed to teach there. Castro hesitated to believe the hype surrounding the big red ‘F’ on the school’s progress report and the student body’s reputation around town. He thinks you can’t judge a school based on the resources they don’t have. Neary’s Advanced Placement classes are proof that students can succeed at DeWitt Clinton.

“I didn’t except the advanced placement kids to be as brilliant as they are,” Castro said. But he believes that his impression of the kids would be the same, even if he’d been placed in a general education classroom.

“Those 12th graders in that AP class were at some point in that 10th grade class with no resources,” he said.

When Students Teach

During Castro’s first week at DeWitt Clinton, the Tri-State area was pummeled by a major snowstorm. Public schools stayed open but Neary, who lives in Connecticut, couldn’t make it in to work. So Castro taught the class by himself instead.

Neary coached Castro on the day’s lesson before class started that day. Volunteer teacher’s sat in to supervise while he led the class. They were impressed, but Castro was more critical of his performance.

“I learned a lot about myself that day,” he said. “When I’m under pressure, I lose my ability to communicate with others.” Castro struggled giving clear instructions to students during the lesson.

But he’s catching on quickly. During an introductory lesson to Macbeth the first week back to school after winter break, Castro seemed to be taking cues from Neary.

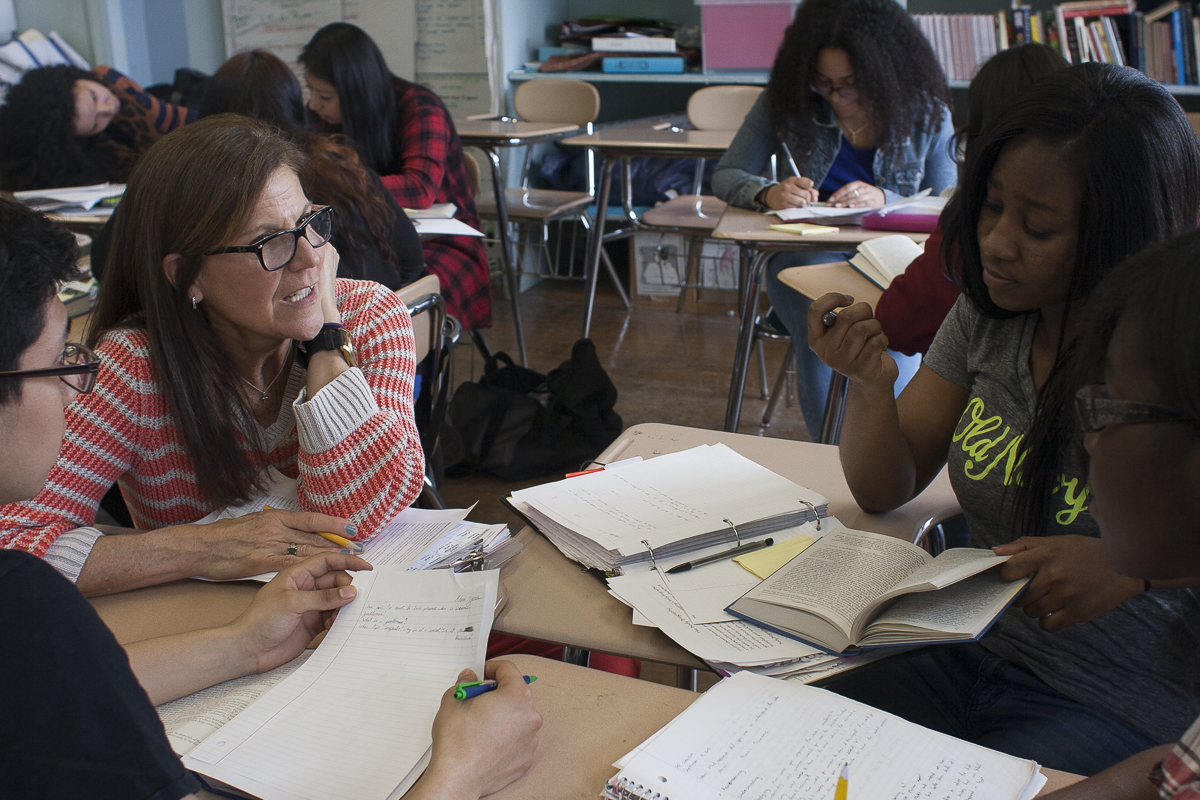

The desks were arranged in a half-circle. Students were split into groups of three and soft chatter filled the room as Neary and Castro deliberated at the front of the room.

Finally, Neary spoke. The students quieted down.

“You are, unbelievably, going to act out the entire Macbeth play in 15 minutes!” she gushed. Her pitch was high and happy.

The class blinked at her. “Excuse me?” one student said bluntly.

Castro seemed wide-eyed and worried. But Neary beamed as she explained that they’d been put into acting companies. Each group was given lines from the play printed on laminated orange notecards. Their job was to get creative and create skits acting out their parts. Neary would stand in the middle and narrate. When she pointed at a group, they’d read the lines and act them out. When she moved to the next group, they’d freeze. The students had about 15 minutes to prepare. This is where Castro came alive.

At each group, he crouched down to eye-level, asking questions, waiting for answers, redirecting those who strayed off-task. The students grappled with the Shakespearean language and then got to work finding props to use for their skits. The classroom, filled with desks, a small assortment of books and pillows for silent reading became a thrift store. Students dug through cabinets and moved tables to create their stages.

When it was show time, Neary stood in the center of the half circle. Castro stood at the back of the room with a timer. In just under 13 minutes, witches bickered and spun in circles, “thou shag-eared villains” were slain with cardboard swords and paper crowns slipped from the curly-headed head of the king. Neary stood in the center spinning in circles pointing from group to group. The kids read their lines, froze, and then read their lines again, rushing to get into position before it was their turn again.

Everyone was beaming by the end of it all.

The class ended with a roundtable discussion about what the play might be about, and about how they’d handle reading a story meant to be seen. The bell rang and students rushed to pack their bags and drag desks back into position. A few lingered, chatting with Castro. Neary stood near her desk, watching.

“I’m really enjoying his presence because he’s very natural with the kids,” she said, later. “I think we’re going to have a really good semester.”