Photo credit: Michelle Brier.

Three years into his job teaching English at P.S. 83 in the Bronx, the principal approached Eric Neuman with an offer: How about taking over the librarian job?

“It is the easiest job in the building,” Neuman remembers his principal saying. “I think you can really make a difference updating it and making it function.”

That’s when Neuman found himself “thrown into the library” with no training, no certification, a circumstance still shared by an estimated one-third of the city’s current librarians.

He later learned that New York State law requires librarians in middle and high schools to obtain a master’s degree in library services— the science of getting the right information into the hands of the right student. Some districts now accept a supplementary certificate which doesn’t require as many credit hours as the master’s degree.

Today, as the city’s 1.1 million public school students are learning entirely online, a trained librarian with a master’s degree in library studies can make the difference between enriched access to learning materials, or not. Barriers to finding books and online resources have increased tenfold since the covid-19 pandemic caused all city schools to close their doors in mid-March.

Yet, in New York City’s approximately 900 middle and high schools, only 600 have library spaces staffed by 350 librarians. Among those 350 librarians, only 200 are certified, estimated Arlene Laverde, president of the New York City School Librarians’ Association.

Neuman’s principal underestimated the job. In 2016, Neuman graduated from Syracuse University with a degree in information sciences. The degree included classes on network security, ethical uses of data, digital literacy and digital citizenship.

Neuman said that going through the degree process opened his mind. He no longer felt like an island, where he was in a room doing his “literature thing.” Instead, he learned that he needed to be “the Swiss Army knife of the building.”

Since March 15th, when school doors shut, Neuman has helped his assistant principal find free resources for her students to access e-books to keep their independent reading program going. He’s helped math teachers find online white board software so they can scribble on their iPads and hold it up to explain how to do math instead of having to type everything out. He’s helped social studies teachers find databases to share with their students to keep their research papers going because they can’t come into the library space and check out a book.

Just because a library has a book in its catalogue doesn’t mean it has that book accessible online. In fact, most of the time it doesn’t.

“I didn’t realize how much more there was to a library than books. I thought if I had books, I had books,” Neuman said. “It has really become about knowing how to find information and knowing how to listen to what kind of information people are looking for, and kind of connecting the two.”

Neuman’s transformation into the librarian he is today was made possible because of New York City’s School Library Services Department partnering with six state universities in New York. He attended Syracuse University at a steeply reduced tuition rate, taking both online and in-person classes.

“I strongly believe in developing relationships with schools with the hopes that those relationships will inform and educate teachers and principals to have a change in mindset to invest in school libraries with certified school librarians,” Director of the city’s Library Services Department Melissa Jacobs wrote in an email.

Laverde, the president of the New York City School Librarians’ Association, also began her job in the library at P.S. 92 in Corona uncertified. “I did not want to be a school librarian, because in all seriousness, I had no idea what a school librarian did, I kind of thought it was a boring type of job,” she said. “And that’s my own ignorance.”

“I’ve known plenty of people who were uncertified who were dynamite in the library,” Neuman said. “And then there are other people who are certified who got certified 20 or 30 years ago and don’t care to stay updated.”

The city’s School Library Services team has also aided librarians to hunt for funding.

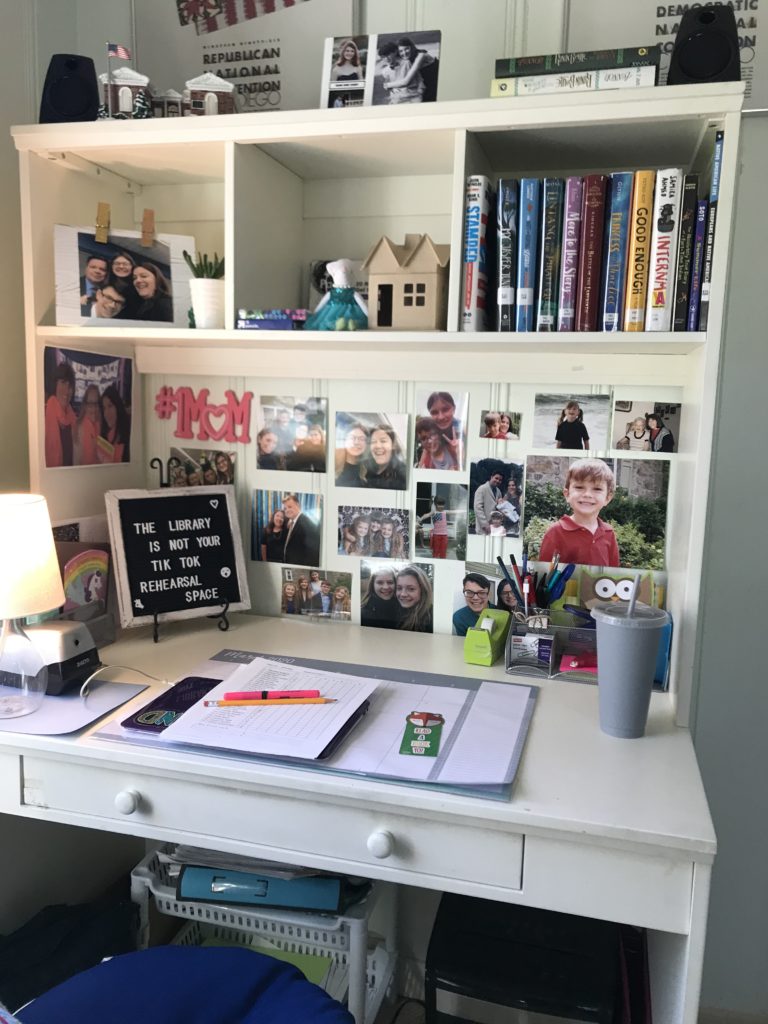

Photo credit: Michelle Brier.

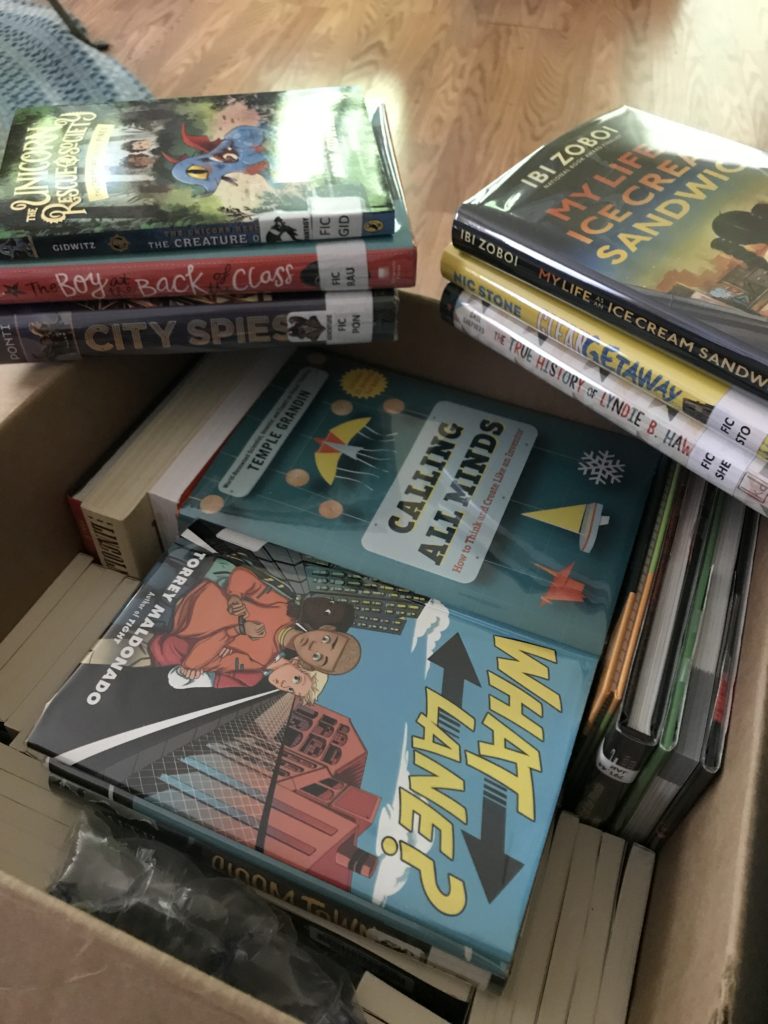

Michelle Brier, a school librarian at M.S. 202 in Queens, recently applied to two grants from First Books, a nonprofit dedicated to providing essential school resources, and the magazine School Library Journal’s partnership with Mathematical Sciences Research Institute. She received both of them, totaling $1,450, which will all go towards buying books for the library next year.

While Neuman and Laverde both say that a lot of what makes a good librarian depends on the person, a master’s in library studies could make the difference between students getting good online access to books or not.

“I researched and researched,” Brier said. “I’m looking all over for grants because there won’t be a lot of money next year.”

Brier also started as an uncertified librarian. It was only until her principal made it clear he would help make the time for her to get her degree could she begin taking the online classes. Sometimes she has to leave work early to get to class, but she says it is making all the difference, especially because she was starting from scratch.

“The pandemic made it clear just how important that knowledge is,” Brier said. “Making a physical library space accessible to every type of learner and learning how to reach students in ways that will not just open new doors but also help them reflect on their experiences, all came from coursework.”