From March 2012, until after the last day of school that June, Shannon Browne, a member of the founding leadership team of Believe Southside Charter High School in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and later its principal, spent her time completing a list of necessary tasks before the school closed its doors. Instead of focusing on the growth and learning of her students and staff, she was busy reconciling accounts, distributing unused supplies, ensuring each student had a new school to attend in the fall, and keeping parents and families informed.

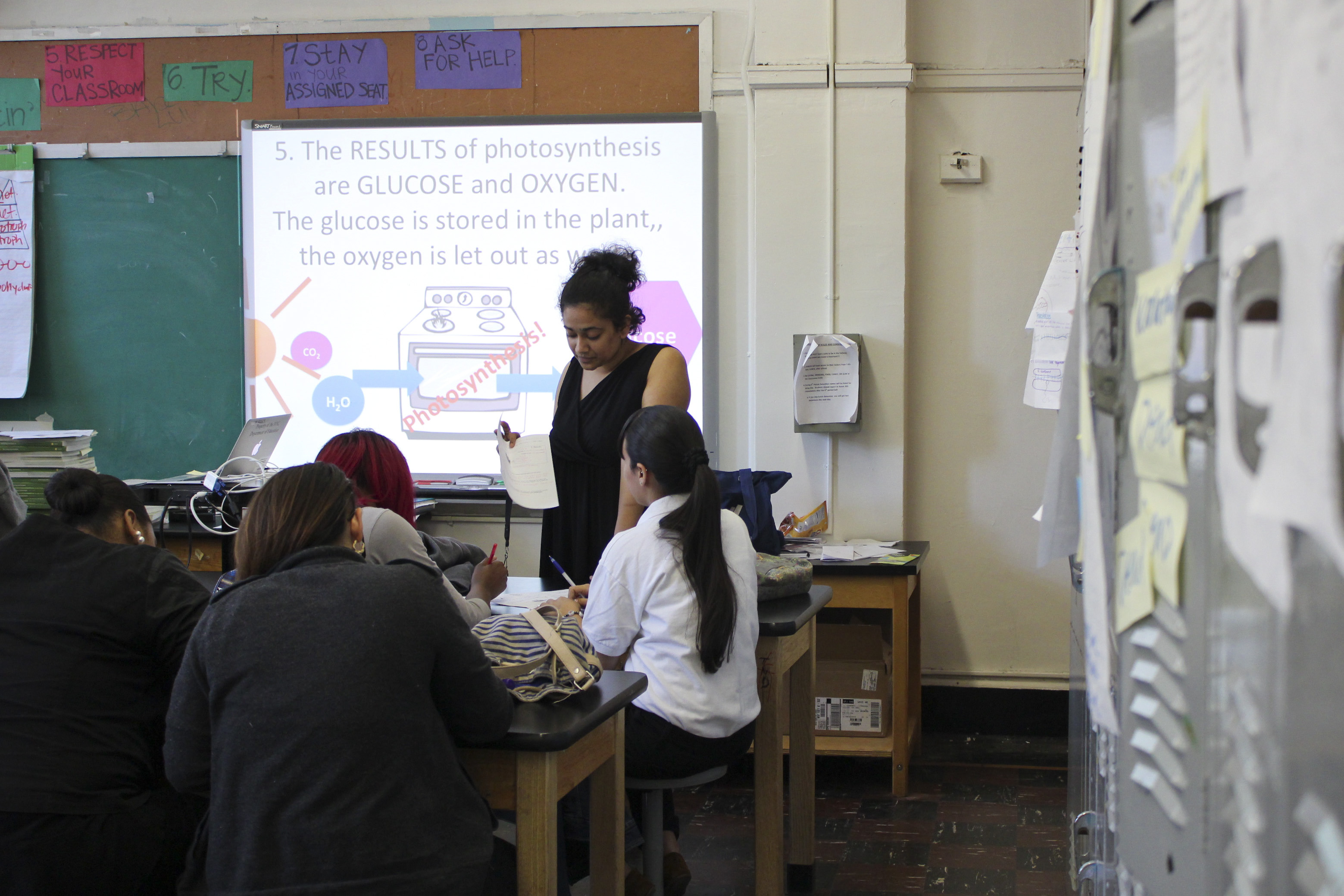

A different type of transition is taking place this year at Bread & Roses Integrated Arts High School in Harlem. Ninth graders Jeremy Rivera and Nakia Watson are trying to navigate their educational paths, after finding out in March that their school will begin the phase-out process next fall. Schools phasing out stop accepting new students; those who remain can opt to stay, or go. Rivera is hoping to transfer to a private school, while Watson believes she will stay put, unsure how the phase-out will affect her school. Teachers and administrators like Pooja Bhaskar, a ninth grade teacher in her first year at the school, and Sabrina Cochran, one of the school’s two guidance counselors, are also uncertain about where they will be next year as the school downsizes.

Both schools illustrate different ends of the school closure spectrum. Believe Southside Charter High School receives public funds but is run privately, like all charters. Its demise was the result of mismanagement by the network that ran it and because its board of trustees did not abide by charter law. Tonia Hucey, a parent who chose to send her son to the charter instead of a public school, was devastated by the news and feels let down again by the education system. Bread & Roses was marked for phase-out because of its poor performance. It received an F on its 2011-2012 Progress Report and Ds in 2009-2010 and 2010-2011. Its graduation rates are low and have been declining since 2008-2009. Students, staff and families alike are unsure what the phase-out will mean for them. Some are excited about getting the opportunity to move on.

In March, the New York City Department of Education’s Panel for Education Policy voted to close two schools and phase out 20 others. This brings to 164 the total number of school closings under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration. This is not solely a phenomenon occurring in New York City; school closures are also handed down from Albany. The New York State Board of Regents has revoked three charters from the 54 charter schools it has overseen in the city and states since 1999. In Philadelphia this year, the city’s School Reform Commission voted to shutter 23 schools and Chicago’s Board of Education will vote May 22 on proposals to close 54 schools considered under-utiilized and under-resourced (schools without science and computer labs, handicap accessibility, air conditioning and playgrounds).

Caught in the middle of a school reform battle over closures and phase-outs are the students, staff and administrators whose lives and educational careers are disrupted. Instead of focusing on learning in the classroom, everyone turns their attention to the necessary protocol for closing up schools or seeking education elsewhere.

The impact is also felt beyond the affected schools. “Under any and all circumstances it is a phenomenon that is taxing on families and communities,” said Warren Simmons, the executive director of the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University.

There are many reasons for school closures and phase-outs, including under-enrollment, under-performance, mismanagement, budgetary issues and violations of charter school law. But the effectiveness of these policies in improving the situation for students has been a source of constant debate. In the past, the strategy had been to provide more resources to struggling schools, explained Eric Nadelstern, a visiting professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, and former deputy chancellor for school support and instruction. This was done “in the hopes that the people responsible for the failure in the first place can somehow redefine the rules, roles and relationships that they helped establish that govern their work.” But, he pointed out, “that never happened, failed organizations don’t reinvent themselves.”

In an opinion piece titled “Schools Closed = kids saved,” published in the NY Daily News in January, Nadelstern talked about the benefits of the closure model: “Simultaneously closing under-performing schools and opening new ones has thrown a lifeline to students and families who would otherwise be consigned to sub-par educations,” he wrote.

As deputy superintendent in the Bronx, he oversaw the closure of six large under-performing high schools and the opening of new schools in their place. He later helped replicate this school reform approach in the rest of the city during his time as deputy chancellor for school support and instruction, closing more than 100 schools and replacing them with nearly 500 new small ones, he said in the NY Daily News piece.

Defenders of school closings, like Nadelstern, point to studies suggesting that the new, smaller schools opened in place of under-performing schools produce better graduation rates. According to a 2012 policy brief by MDRC, a nonprofit education and social policy organization, students studying at a group of small schools had a four-year graduation rate of 67.9 percent, compared to 59.3 percent for students who wanted to attend a small school, but were assigned by lottery to other New York City high schools, which, on average, are larger and older.

But not everyone agrees with this approach. “If you bought a car, would you simply want a guarantee that if it broke down we’d give you a new one every two or three years or do you want a guarantee of a high capacity, well-performing automobile?” asked Simmons. “It is the same thing with schools.”

Simmons produced a report in April 2012 with the New York City Working Group on School Transformation, which suggested an alternative to school closures: an idea called Success Initiative Zones.

Success Initiative Zones would pair high-performing schools with low-performing schools with similar student populations to share successful educational practices in an effort to strengthen the foundations of those flailing schools. In this way, the group hopes to save the schools before they are marked for closure or phase-out.

According to Simmons, this is not a new policy. It is something that has existed for decades and was even created by the New York City Department of Education. The report sought to remind the department of its previous success with these mentorship-like programs and to update the reform. It was formally presented to the department and Simmons hopes the report will inform future education reform decisions, especially when the city elects a new mayor in November.

He also hopes that the Department of Education, along with the new mayor, will look at school failure in broader terms. “A school closure assumes that everything that went wrong in the school is the responsibility of the school and that places an enormous responsibility on the school and on students and families to vacate,” he said.

At Bread & Roses, enrollment through an ‘Educational Option’ system, a formula designed to admit students with a wide range of abilities, means that some of its students are those who would not be accepted at more selective schools in the neighborhood. “Many of the schools in the area won’t necessarily take our kids, but we take those kids, we educate those kids, we graduate those kids,” Bhaskar said at the school’s first closing hearing in March. At the hearing, students and teachers asked the department for more time to see the positive effects of changes made in recent years through other reforms.

More time was something the parents, teachers and administrators at Believe Southside Charter High School in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, sought from the New York State Board of Regents. The school’s charter was revoked in 2012 because the network in charge of running the school had mismanaged money and because its board of trustees did not abide by charter law. There should have been five trustees on the board, and there were only three, so legal decisions about the school could not be made. Parents like Hucey rallied together to come up with names of possible trustee appointees and other strategies to stave off the school closure. Their work was all for naught, as the school closed and they had to focus on making the transition to new schools a smooth one for their children.

The closure was hard on Believe Southside’s students because it meant severing the nurturing, family-like community that had grown from the time the school opened in 2009 until its closure in 2012. This echoes a downside to school closings noted by Simmons – the missed future opportunities to have alumni serve as important connections and resources in the community to future generations of school kids. “Let’s also not forget that schools, in addition to being academic institutions, are also cultural and historical and social resources in communities in neighborhoods,” he said.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Click on the images throughout this article for the personal stories of Believe Southside Charter High School’s closure and Bread & Roses phase-out, as told by the administrators, students, staff and parents.

Explore the timelines of the transitions at the two schools below and view some of the documents that have been used in the processes of closure and phase-out.